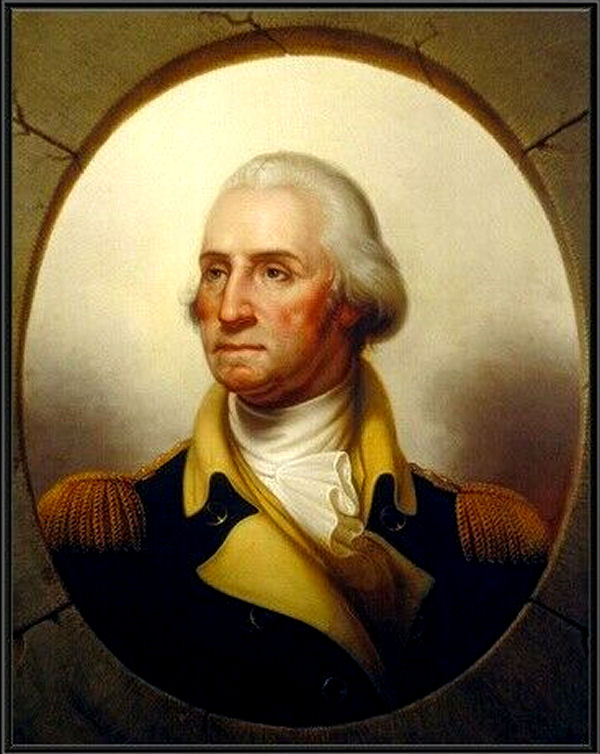

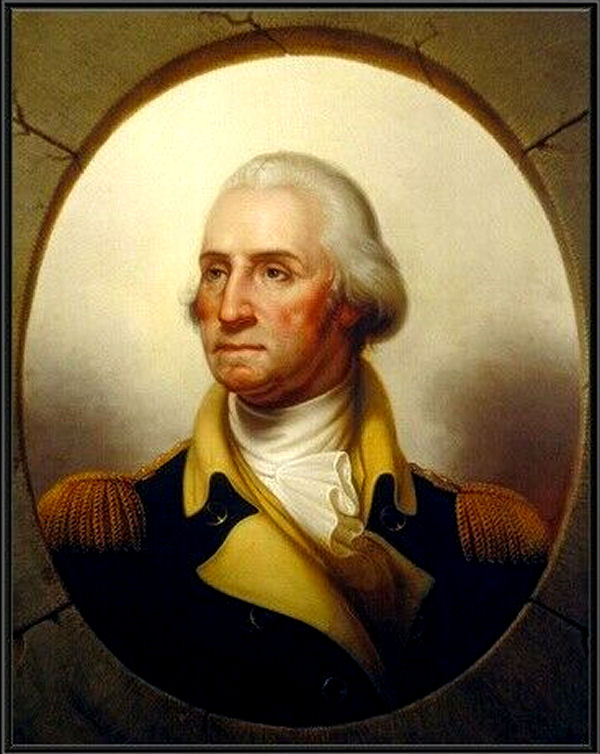

George Washington Slept Here

It’s become a cliché to claim that ‘George Washington slept here.’ It was once said that if George Washington slept in every house in which he is claimed to have slept, they would be more numerous than Dunkin Donut shops. A more modern variation of that sentiment would use Starbucks coffeeshops as the measure.

In any case, Bedford County can be proud of the fact that George Washington did indeed sleep in at least one house ~ the two-storey stone structure believed to have been built by Thomas Smith, and owned by David Espy in the year 1794. George Washington was only a Colonel commanding a unit of Virginia Provincial troops when he took part in General John Forbes’ campaign to capture Fort Duquesne from the French in 1758. At that time, Washington was not the exalted demi-god that generations of Americans have made him out to be since his service in the American Revolutionary War or as the nation’s first President. He was just a Colonel of Provincial troops. During the French and Indian War, the British Army regulars viewed all Provincial troops as inferiors. Although he was in a position of command, Washington was still a Provincial and was probably not considered by Colonel Henry Bouquet to be his equal.

At the time that Fort Bedford was being garrisoned, there were possibly three structures in which officers could make their quarters: the large stone house of Christopher Lems to the west of the fort, the log and stone building on the opposite side of the road known as the King’s House or the Commandant’s House, and the tavern at the foot of the hill owned by Garrett Pendergrass. Colonel Bouquet is known to have made his quarters in the Lems house, which is why it became known as the Bouquet House. Whether other officers stayed in any of the three structures is not known. In any case, none of the three buildings still stand today, so if Washington had stayed in any of them is inconsequential. More than likely, having been a Provincial officer he would have made his quarters in one of the log buildings constructed in the redoubt in which his regiment was quartered ~ which was located in the vicinity of where the fairgrounds are located today.

The next time that George Washington came to this region was in October of 1794. The Whiskey Rebellion came about with the enactment of an Act of Congress that repealed a previous tax on distilled spirits, but replaced it with a new one. When the excise officers announced to the residents of the western counties of Pennsylvania that the new tax would be collected, by force if necessary, they organized the first rebellion to test the new national government’s resolve. There is a widespread misconception about the basis of the Whiskey Rebellion. The general belief is that farmers converted their dry grain into liquid whiskey because it was more expensive to transport the dry grain to the eastern markets than it was to transport the whiskey. One pound of dry grain weighs the same as one pound of whiskey. The reason that distillers and tavern and innkeepers objected to the tax was because they could get a higher price for whiskey than they could for dry grain, and the tax appeared to discriminate against them when other commodities were unaffected. Those who advocate the idea that the farmers made whiskey from the dry grain because it was easier or cheaper to transport that way fail to explain how the eastern buyers could bake bread out of the whiskey. If they needed the dry grain, they needed the dry grain and distilled whiskey would not substitute for dry grain.

George Washington, in the first and only instance of a sitting President exercising his role as ‘Commander in Chief’ of the army, led a division of Federal troops westward, coming to Bedford County by way of Cumberland, Maryland. He met a second division led by General Henry Lee over the Forbes Road. The two divisions met at Bedford on the 19th of October. The troops were assembled and Washington reviewed them before retiring for the night at the home of David Espy. Despite the fact that past owners of the Jean Bonnet Inn have claimed that the troops were paraded on the fields adjacent to the stone tavern, there is no proof of the claim. The fields to the southeast of the fort ~ in the vicinity of where the Bedford Area High School is located today ~ were where the troops were trained, exercised and paraded while Fort Bedford was garrisoned, and that is where the troops in 1794 were probably paraded.

A common belief is that George Washington spent three nights in Bedford ~ giving him ample time to sleep in various other buildings. But the available evidence suggests that he spent only one or at the most two nights here. The belief that he was at Bedford for more than one day and one night probably came from a letter that Bartholomew Dandridge wrote to the Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson, on the 18th in which he stated: “The President will leave this place [Fort Cumberland] early tomorrow morning on his way to Bedford, where ‘tis likely he will be detained three of four days.”

President Washington wrote a letter to Jefferson, dated Fort Cumberland, October 18, 1794. He arrived with his division of the army at Bedford the following day, the 19th, at the same time that General Henry Lee arrived with his division. Washington is known to have written a letter to General Henry Lee dated Bedford, October 20, 1794 in which he started out by stating: “Being about to return to the seat of government…” At what time of the day he wrote out the letter is not known ~ it could have been in the morning, the afternoon or the evening. What is known is that his next letter, dated: Hartley’s, Tuesday Evening, October 21, 1794 reveals that he was at that time at the tavern owned and operated by William Hartley in Snake Spring Township, eight miles east of Bedford. The claim that Mrs. Hartley and Washington played a game of backgammon is possibly true. He no doubt ate supper at Hartleys and relaxed a bit before continuing on his journey east.

A normal day’s travel by horse in the 1700s was twenty to thirty miles. So it would have taken Washington only half a day to reach Hartley’s Tavern. Washington next wrote a letter on the 26th from Wright’s Ferry on the Susquehanna River. At 124 miles distance, if he had stayed overnight at Hartley’s and not set out until the 22nd, he might not have arrived at Wright’s Ferry until the 27th. It would appear that although he made a stopover at Hartley’s, he probably did not stay overnight there.

From the available evidence, which exists only in the letters written by George Washington, the only things known for certain is that he spent the night of 19 October, and possibly the night of the 20th also at the Espy House and in the evening of the 21st he was at Hartley’s Tavern. And within four days he had traveled 124 miles to Wright’s Ferry, suggesting that he had not stayed overnight at Hartley’s.

Although George Washington is known to have stayed overnight at the Espy House at least one night, nothing further can be stated with surety. Nor can the claim that he stayed overnight in any other building in this region be confirmed. The claim that he also stayed overnight at the Fraser Tavern is purely fiction. The claim that he stayed at the Jean Bonnet Inn (then the Old Forks Inn) is purely fiction ~ nor is there any proof that he 'paraded the troops' in the fields adjoining the Old Forks Inn.