Fort Bedford

While most of the things we know about Fort Bedford are accurate, some misconceptions are perpetuated about the fort around which the village of Bedford grew.

The most important misconception that people have about Fort Bedford is that they think that it was constructed first and foremost as a defensive structure into which everyone ~ soldiers and townsfolk alike ~ would flee when attacked by the French and their Amerindian allies. While the structure was most definitely constructed for defense, it was for the defense of supplies for which it was primarily constructed ~ that included bags of grain, barrels of rum and other ‘perishable items’ such as salted meat along with tools, weapons and such. It was a supply depot, in other words. Three log buildings were built within the stockade walls, but they were not built to house men. They were built to house wooden barrels, woven reed baskets and cloth sacks filled with supplies. Use as a defensive structure for the safety of people was only a secondary purpose of the structure.

E. Howard Blackburn, in his History of Bedford and Somerset Counties, Pennsylvania, published in 1906, stated: “On the Arrival of General Forbes at Raystown, on September 15, the condition of affairs in and about the fort was by no means orderly. Here within the narrow limits of a military fort, were congregated an army of nearly six thousand men, besides sutlers, clerks and wagoners…” Mr. Blackburn created an image that his fellow historians at the beginning of the 20th Century embraced ~ 6,000 plus men within the narrow limits of the military fort ~ not around, but within the fort. Now the stockade fort was estimated by Hugo Frear, from available records, as having measured 250 by 280 feet. That would have encompassed roughly 70,000 square feet. That seems like a gigantic area. And so 6,000 men, if they each took up only one square foot each, would have had for their own use about 11-1/2 square feet each – imagine a spot measuring 3 feet by 4 feet – that is what each man would have had to himself. It would have been a little cramped, and kind of difficult to move around. But wait ~ there’s a lot of people (this author included) whose bodies require a slightly bigger than a one foot square space. So assuming that half the men were not skinny bean-poles, and would have taken up two square feet spaces, that would mean that instead of each one having 11-1/2 square feet to themselves, they would have had only about six square feet ~ or a space measuring about 2 feet by 3 feet. Then add the backroll and other accoutrements that each man had to carry with him. And once you crammed everyone into the fort, they would all have had to stand around like we experience today in a crowded elevator, trying not to breathe too heavily against the neck of the person standing in front of us. The stockade fort was simply not the type of fort in which everyone spent their whole day. Those forts only existed in cowboy and wild west movies. And speaking of movie forts ~ did you ever see one in which 6,000 men were congregated? The largest number of soldiers shown in movie forts was probably fifty to one hundred.

As mentioned, although most people who read descriptions of the fort, or see reproductions of it, believe that the buildings within the stockade walls were used by soldiers in which to eat, sleep and spend their days ~ that wouldn’t have been the case. The soldiers slept in log-construction buildings. But those buildings were placed within four redoubts located to the west of the fort stretching from about the present-day intersection of Pitt and West Streets to just beyond where the fair grounds are located.

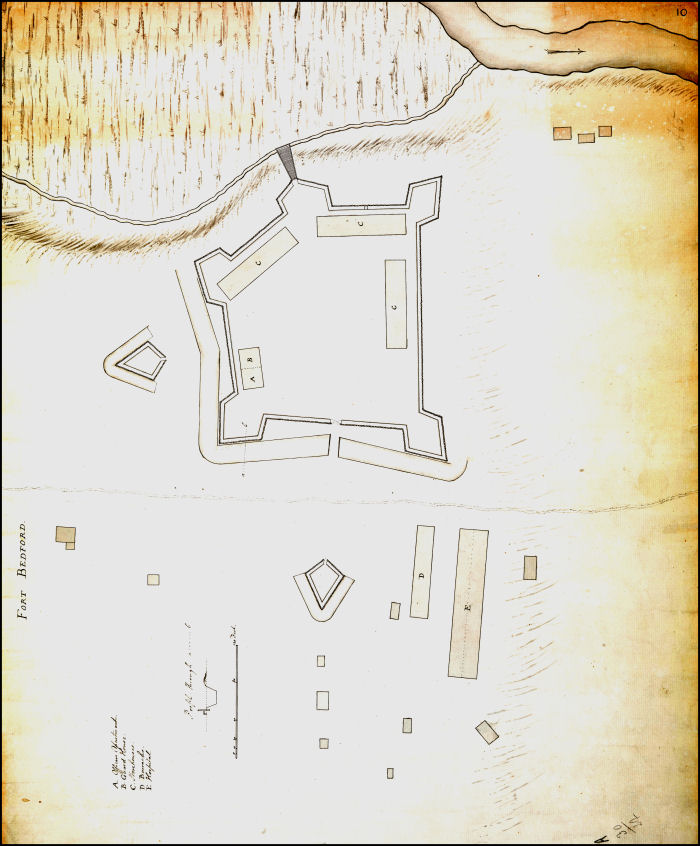

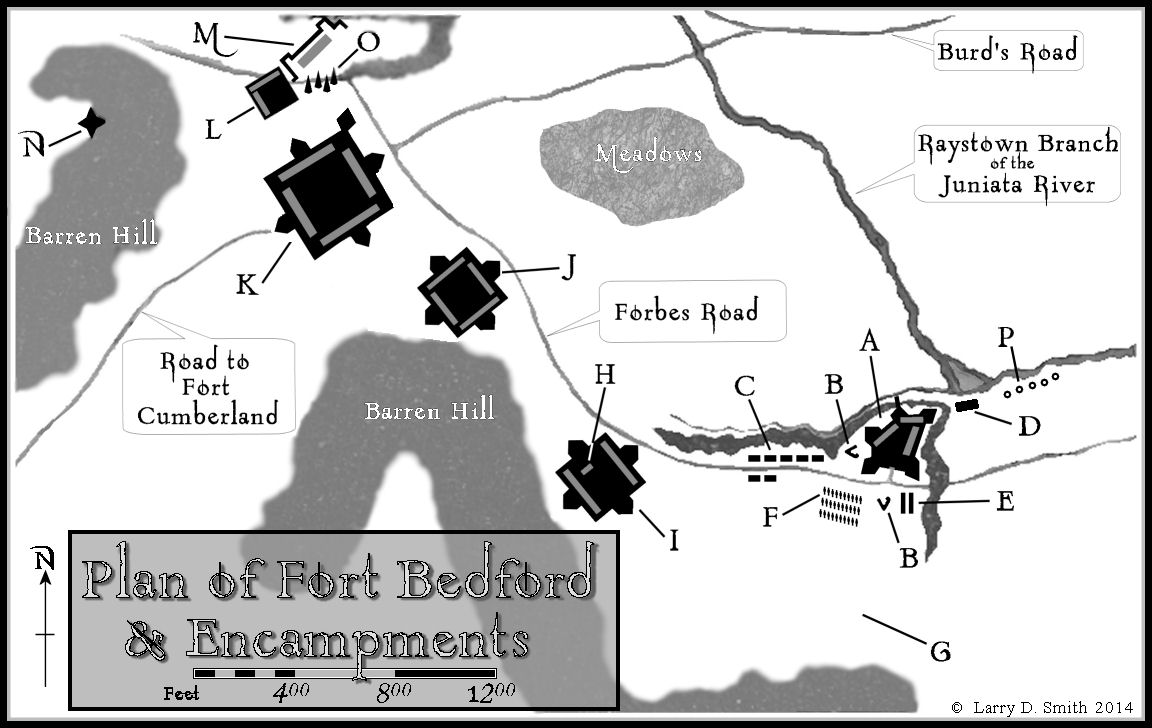

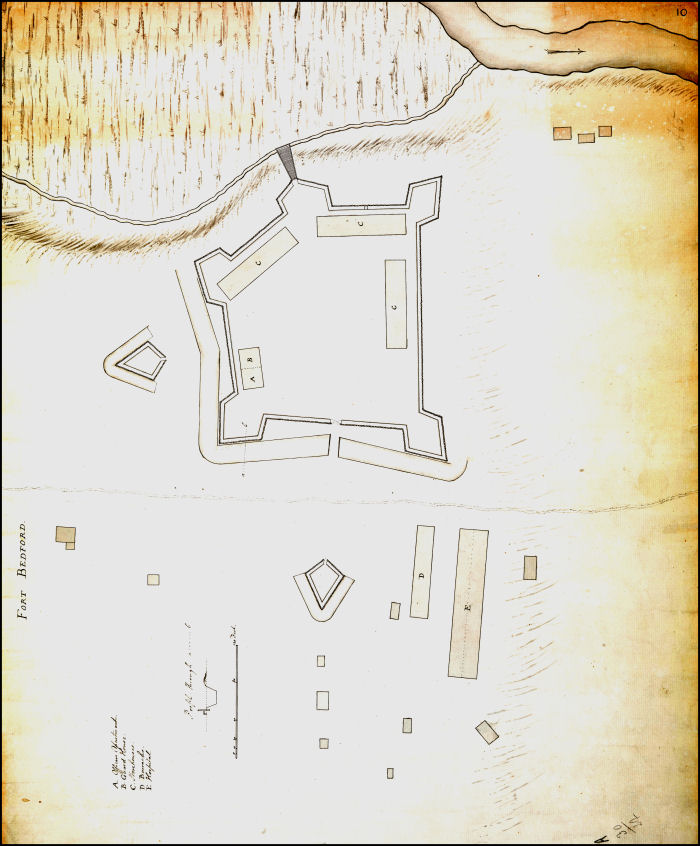

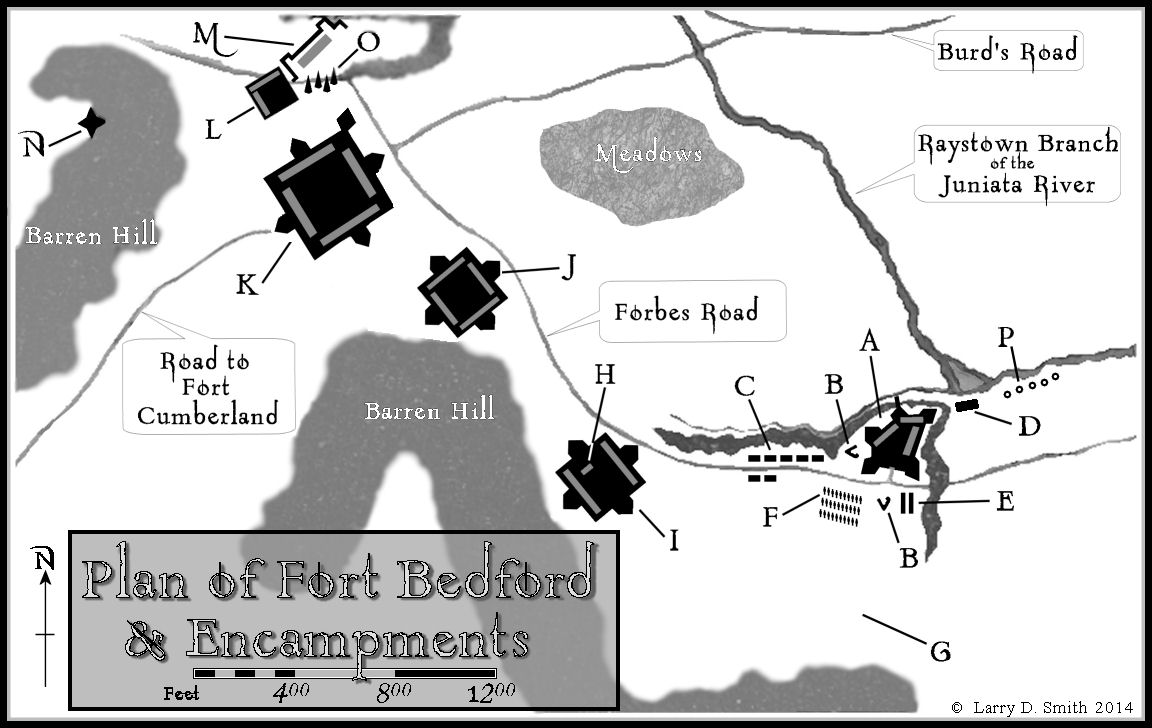

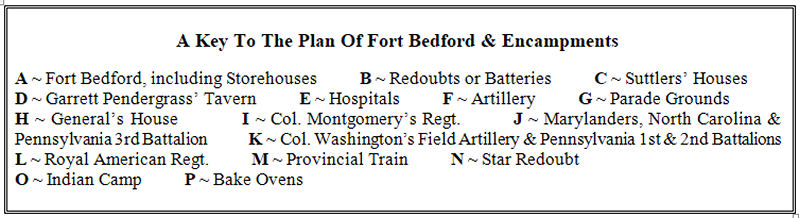

The plan shown below is based on the 1758 plan of Fort Bedford by J.C. Pleydell. It shows the layout of the redoubts to the west of the stockade fort.

The redoubts were constructed of the ground and rocks dug up from their centers and also from ditches or moats surrounding them. The soldiers would begin to dig a large, square hole in the ground, piling the loosened dirt and rocks around the perimeter of that hole. As they dug down, the walls would grow higher, and that height would be augmented by dirt and rocks dug up in a ditch or moat surrounding the outside of the walls. The floor or base of the redoubt would be leveled as much as possible and then log structures would be constructed inside the earthen walls to house the soldiers.

Another misconception that people tend to believe in regard to forts such as Fort Bedford is that teamsters would drive their wagons into the stockade fort and then unhitch them and tie the horses or oxen somewhere inside the stockade. It was undoubtedly necessary for wagons to be driven into the stockade for the purpose of having the supplies they were hauling to be unloaded and the supplies carried into the storehouses. But the horses and wagons could not remain inside the stockade; it would have become too crowded. They would have been led out of the stockade and placed in a fenced-in pasture nearby. In the Pleydell Map, 'meadows' are shown to the northwest of the stockade fort.

And speaking of animals: while adventure tales, such as the one Hervey Allen wrote are made all the more exciting by imagining the hustle and bustle of the fort being accented by the sounds of sheep and cows being driven into and sheltered in the fort, there simply would not have been room for livestock inside the fort. The meadows on the opposite, north side of the river were where livestock could have been corralled within fenced areas. Sentries assigned to watch over those fenced in livestock would have guaranteed the safety of the animals. Just to give an idea of the large number of animals passing Fort Bedford: On the 1st of October 1758, Adam Hoops, a livestock trader from Carlisle reported to Colonel Bouquet that since June ~ just within four months’ time ~ he had sent through 1,647 beeves and 684 sheep “Exclusive of the Cattle and Sheep from Virginia.” Granted, a drove of beef cattle would have been corralled only a short period of time before being sent on westward to the troops at Fort Ligonier or eaten here, but to corral two and three hundred head of cattle for just a day or two would require logistical control.

The fields to the south of the stockade fort were utilized for drilling and exercising the troops. Another misconception about forts during the French and Indian and the American Revolutionary Wars, supported by movies and television shows was that the soldiers spent their days pacing back and forth on the ramparts looking out over the landscape for attacking French soldiers and Indians. Granted, while some soldiers would have done that during their duty periods, the majority of them were kept busy tending to the livestock and drilling and exercising to keep from getting lazy. In regard to Fort Bedford, the majority of soldiers were kept busy working at clearing brush, trees and rocks in the work of laying out the road between Fort Bedford and Fort Ligonier.

The ‘official’ date claimed for the naming of the fort has been set at 13 August 1759 as noted by Howard Blackburn: “To General Stanwix belongs the responsibility or credit in changing the name of this fort from ‘the Fort at Raystown’ to the Fort Bedford, which change appears by a letter from General Stanwix, dated August 13, 1759, to Governor Denny, this being about one year from the date of the building of the fort.” The quote comes from Howard Blackburn’s History of Bedford and Somerset Counties, Pennsylvania. Blackburn apparently did not read Colonel Henry Bouquet’s papers. If he had, he would have found a letter written by the livestock trader, Adam Hoops, in December 1758 on which he gave the dateline: Fort Bedford. Keep in mind that the name ‘Bedford’ was not already associated with anything at that time. General Stanwix’s supposed official naming was eight months away. The Proprietary Manor was three years away. The town was eight years away. The township within Cumberland County was nine years away. And the county was thirteen years away. In order for a livestock trader to come up with the name 'Bedford,' he must have heard it being used by the British soldiers at the fort. Prior to 13 August 1759 (when it was claimed that General Stanwix initially named the fort), the name Fort Bedford was used on seventy-three letters in the collection of papers of Henry Bouquet; the word Bedford was used on three other letters; and the phrase Camp near Bedford was used on two separate letters. Seventy-nine instances (including the Hoops letter at the end of 1758) of the use of the name Bedford to denote either the fort or the camp, prior to when General Stanwix used it, tend to point toward General Stanwix as not being the originator of the name.

And then there is the ‘Capture of the First British Fort by American Rebels’: James Smith and his Black Boys incident of 1769. As late as June 1764, the fort was still being garrisoned by the British Army. John Randolph, for the colony of Virginia was investigating the alleged misconduct of Colonel Adam Stephen. The report that Randolph filed in December 1764 noted that in the prior year of 1763, Colonel Stephen had engaged with contractors to supply the army “with a quantity of fflower [sic] to be delivered at Fort Cumberland and Bedford and a number of Beeves to be delivered at Fort Bedford…” and that “in the Spring of the following year [1764] Colo Stephen reced a Ltr from Capt Ourry Commandant at Fort Bedford…to receive what he could deliver by the 4th of June at Bedford…” The report therefore confirms that Fort Bedford was being garrisoned by the army and commanded by Lewis Ourry definitely up to June 1764. The only contemporary document to suggest when the British troops were removed from the fort is a petition by Garrett Pendergrass to the Provincial Governor, John Penn in October of 1766. In that petition for recompense because his property had been confiscated by the Proprietors, Mr. Pendergrass noted that “since the King’s Troops evacuated that Fort, and the Avenues thereof, the Improvements of your Petitioner have been surveyed, under your Honor’s Warrant afsd, for the use of the Honorable the Proprietaries.” From that document, it may be assumed that the King’s Troops, meaning the British, were no longer garrisoning the fort by October 1766. The fort would have been garrisoned thereafter by Cumberland (and later Bedford) County Militia for the safety of the local inhabitants up to and during the Revolutionary War. The only source of the so-called ‘capture’ of Fort Bedford by American rebels is the autobiography of James Smith. No record of the incident was recorded in the papers collected together in the Pennsylvania Archives. No record of the incident was recorded at the Cumberland County Court House. The only source of any information on the incident was written by James Smith himself, which he published in 1799, thirty years after the incident. He claimed to have executed his capture of the fort on 12 September 1769 ~ three years after the British troops evacuated the fort.

During the year 1769, the Amerindians had made a number of incursions into the region around the three-year-old town of Bedford. As noted by Smith: “yet, the traders continued carrying goods and warlike stores to them.” Alarmed at the situation, a number of persons plundered the offending traders’ stores, which they then destroyed. Although their actions were ostensibly for the safety of their fellow Euro~American settlers, the persons who plundered the traders’ goods were arrested. Whether they were justified in attempting to deprive the Amerindians of ammunition was inconsequential in regard to the fact that ordinary citizens were not allowed to take the law into their own hands. The arrested persons were fettered in iron shackles and confined in the guard-house in Fort Bedford. The fact that the arrested persons were confined in the fort is not as significant as it might initially appear. Being held prisoner by red-coated British soldiers wielding bayonet-fixed muskets in a formidable stockade-surrounded fort is the stuff of a dramatic movie. But, as noted, the red-coated British troops had evacuated the fort three years earlier. Activity at the fort, keeping watch for any attack by the Amerindians no doubt came to an end when Pontiac’s War was quelled by Bouquet in 1765, and that is probably why the British army evacuated the fort by the following year. Although James Smith did not state it in so many words in his memoirs, the persons arrested for plundering the traders’ goods would have had to have been confined somewhere. In 1769, the town of Bedford was not a county seat. The ‘county’ was two years away. There was no county gaol or prison at that time. There was, in fact, no borough in 1769; Bedford was simply a small frontier village. The rule of law in the region was enforced by the Cumberland County authorities, such as the sheriff and his deputies. So when James Smith made the statement in his memoirs that “some of these persons, with others, were apprehended and laid in irons in the guard-house in Fort Bedford…”, the assumption should not be made that it was because the ‘British army’ was in control, or even present at the time, but rather because the fort, though in the process of decaying, would have been the most logical building, if not the only ‘public’ building, in which to confine the prisoners. Smith had engaged a friend by the name of William Thompson to gain information on where and how the prisoners were being held. When he and seventeen of the ‘Black Boys’ arrived near the village, Smith met up with Thompson, who informed him that “the commanding officer had…ordered thirty men upon guard.” James Smith did not state that the fort was garrisoned by the British Army. By calling him the ‘commanding officer,’ the man heading the provincial authority could have been a sheriff or a provincial militia officer. Also, in regard to this point, the number of men ‘ordered upon guard’ did not necessarily mean that that number of men actually responded for the guard duty. By stating that the ‘commanding officer’ ordered thirty men to guard the prisoners, Smith implied that his little band of eighteen men going up against a superior force of thirty, would be more daring than it might actually have been. At day-break, Thompson told Smith that the gate was finally opened and there were only three sentinels ~ the rest of the guard were ‘taking a morning dram’, suggesting that they were off getting drunk. Smith completed his narrative of the event with: “I then concluded to rush into the fort, and told Thompson to run before me to the arms, we ran with all our might, and as it was a misty morning, the centinels scarcely saw us until we were within the gate, and took possession of the arms. Just as we were entering, two of them discharged their guns, though I do not believe they aimed at us. We then raised a shout, which surprized the town, though some of them were well pleased with the news. We compelled a black-smith to take the irons off the prisoners, and then we left the place.” How Smith knew that some of the townspeople were ‘well pleased with the news’ is not explained, and as no one felt compelled to record the event other than Smith himself, we will never know. So while Smith and his Black Boys might have truly attacked the fort, it would have been Cumberland County Militia, rather than red-coated British troops, and only three who were in control of the fort at the time. Since Smith and his Black Boys left as quickly as they came, the fort itself was not really ‘captured’ by American rebels. Being captured would imply that it was taken possession of and held for a period of time. Smith and his men, according to his own words simply rushed in, stole some guns, freed the men who had committed a crime and ran off. The incident didn’t make much of an impression on anyone at the time. It wasn’t even reported by any of the local justices of the peace or the sheriff to the Cumberland County Court. Instead of flouting that “Fort Bedford was the first British fort to be attacked and captured by American rebels,” it should more accurately be stated that Fort Bedford was the first already evacuated British fort with no British soldiers present to be attacked and immediately abandoned by a self-appointed vigilante group. But that doesn’t sound very dramatic and noble, so James Smith sort of embellished the tale and laid claim to an honor he really didn’t deserve. The lack of accuracy doesn’t prevent re-enactors from staging mock attacks on the fort in present-day celebrations, though.

Fort Bedford was a strategically important supply depot that ensured the success of Forbes Campaign to capture Fort Duquesne and should be celebrated for that. Its importance is not diminished by the fact that it wasn’t physically attacked by the French or their Amerindian allies.