![]() The earliest history of West Providence Township is closely tied to the events of the French and Indian War. The building of Burd's Road in 1755 brought the first Euro~Americans into the region other than the occasional traders and adventurers, such as James Dunning, John Ray and Thomas Kinton. What should be noted is that James Burd wrote a letter on 17 June 1755 to Mr. Richard Peters, the Secretary of the Province of Pennsylvania and Clerk of the Provincial Council. In that letter Burd noted: "Our Company upon the Roads are in two Divisions, the foremost Division this Night will be about five Miles ahead of Us, and to-morrow morning We shall finish here and march up to them to Ray's Town." The letter was written from 'Allogueepy's Town'. Two days later, Burd wrote another letter to Mr. Peters from 'Ray's Town'. Now it is very important to remember that the addition of the word 'town', which was derived from the Old German word "zaun" suggested two or more buildings surrounded by a fence or wall, which was the way that many trading posts were constructed. In the 1700's, the word did not mean to suggest that there was a 'village' anywhere in the vicinity. That is a more recent interpretation.

The earliest history of West Providence Township is closely tied to the events of the French and Indian War. The building of Burd's Road in 1755 brought the first Euro~Americans into the region other than the occasional traders and adventurers, such as James Dunning, John Ray and Thomas Kinton. What should be noted is that James Burd wrote a letter on 17 June 1755 to Mr. Richard Peters, the Secretary of the Province of Pennsylvania and Clerk of the Provincial Council. In that letter Burd noted: "Our Company upon the Roads are in two Divisions, the foremost Division this Night will be about five Miles ahead of Us, and to-morrow morning We shall finish here and march up to them to Ray's Town." The letter was written from 'Allogueepy's Town'. Two days later, Burd wrote another letter to Mr. Peters from 'Ray's Town'. Now it is very important to remember that the addition of the word 'town', which was derived from the Old German word "zaun" suggested two or more buildings surrounded by a fence or wall, which was the way that many trading posts were constructed. In the 1700's, the word did not mean to suggest that there was a 'village' anywhere in the vicinity. That is a more recent interpretation.

![]() The Warrior Ridge parallels Tussey Mountain, to the east. A gap in the Warrior Ridge exists where the Juniata River cuts through it. The gap is shown on the 1759 map produced by Nicholas Scull with the name: Allaguippy's Gap. The portion of Warrior Ridge to the north of the gap is sometimes locally referred to as the Aliquippa Ridge. Queen Allaquippa is often cited as a resident of this region, and from whom the name for the gap was derived. But there is no evidence to prove that the Seneca woman sachem ever resided here. Likewise, there is no evidence to prove that a village was in existence when Burd and his men cut the road through the gap. If there had been a village in the vicinity, there is no reason for Burd to not have mentioned it.

The Warrior Ridge parallels Tussey Mountain, to the east. A gap in the Warrior Ridge exists where the Juniata River cuts through it. The gap is shown on the 1759 map produced by Nicholas Scull with the name: Allaguippy's Gap. The portion of Warrior Ridge to the north of the gap is sometimes locally referred to as the Aliquippa Ridge. Queen Allaquippa is often cited as a resident of this region, and from whom the name for the gap was derived. But there is no evidence to prove that the Seneca woman sachem ever resided here. Likewise, there is no evidence to prove that a village was in existence when Burd and his men cut the road through the gap. If there had been a village in the vicinity, there is no reason for Burd to not have mentioned it.

![]() Alternatively, the name for the gap may have been derived from Allaguippas, an Iroquois chief. But, as with Queen Allaquippa, there is no evidence to prove that the Iroquois chief, Allaguippas ever resided in the vicinity. Despite the lack of hard evidence to prove from which of the two Amerindians the name was derived, one or the other must have influenced the region in some manner in order for the name to be chosen for the gap.

Alternatively, the name for the gap may have been derived from Allaguippas, an Iroquois chief. But, as with Queen Allaquippa, there is no evidence to prove that the Iroquois chief, Allaguippas ever resided in the vicinity. Despite the lack of hard evidence to prove from which of the two Amerindians the name was derived, one or the other must have influenced the region in some manner in order for the name to be chosen for the gap.

![]() Much is made of the fact that a site to the east of the Aliquippa's Gap was once called "Bloody Run". Bloody Run was first mentioned in a listing of pack horses that died or were stolen during the Forbes Campaign. A List of the Different Breads of Horses Killed & Taken by the Enemy was compiled at some time in 1759 (the exact date is not stated) by Callender and Hughes. Captain Robert Callender and Mr. Barnabas Hughes were in charge of the divisions of pack horses carrying the supplies during Forbes Campaign. An inventory of the horses was taken near the end of the year 1759. William White was in charge of Brigade #4. He reported that one horse 'gave out' (i.e. died from exhaustion) "at Bloody Run by ye Officer making me drive two hard."

Much is made of the fact that a site to the east of the Aliquippa's Gap was once called "Bloody Run". Bloody Run was first mentioned in a listing of pack horses that died or were stolen during the Forbes Campaign. A List of the Different Breads of Horses Killed & Taken by the Enemy was compiled at some time in 1759 (the exact date is not stated) by Callender and Hughes. Captain Robert Callender and Mr. Barnabas Hughes were in charge of the divisions of pack horses carrying the supplies during Forbes Campaign. An inventory of the horses was taken near the end of the year 1759. William White was in charge of Brigade #4. He reported that one horse 'gave out' (i.e. died from exhaustion) "at Bloody Run by ye Officer making me drive two hard."

![]() Many and varied 'stopping places' existed along the Forbes Road during the campaign to capture Fort Duquesne from the French. The stopping places included anything from proper (i.e. British Royal Army approved) fortifications, such as Fort Lyttelton and Fort Bedford to redoubt protected sites such as the Shawnee Cabins and Fort Dewart to unfortified but commonly known landmarks, such as Dunnings [Crossing], the Snake Spring and Bloody Run ~ all three of which were included in the Accounts of Pack Horses reported by Callender and Hughes in 1759. There exists no record in either the papers of Henry Bouquet or the published Pennsylvania Archives to suggest that any type of settlement or village existed at any of the three landmarks last noted. They were probably well known locales where horses could be rested, and more importantly watered and refreshed, before moving on to the next point along the Communication.

Many and varied 'stopping places' existed along the Forbes Road during the campaign to capture Fort Duquesne from the French. The stopping places included anything from proper (i.e. British Royal Army approved) fortifications, such as Fort Lyttelton and Fort Bedford to redoubt protected sites such as the Shawnee Cabins and Fort Dewart to unfortified but commonly known landmarks, such as Dunnings [Crossing], the Snake Spring and Bloody Run ~ all three of which were included in the Accounts of Pack Horses reported by Callender and Hughes in 1759. There exists no record in either the papers of Henry Bouquet or the published Pennsylvania Archives to suggest that any type of settlement or village existed at any of the three landmarks last noted. They were probably well known locales where horses could be rested, and more importantly watered and refreshed, before moving on to the next point along the Communication.

![]() In the absence of public records, local traditions arise to fill gaps in the historical record. Since no one can prove them to be wrong, those traditions are accepted as truth. Each time that they are repeated, the traditions take on more legitimacy. Eventually, a tradition becomes a fact. That is how Fort Defiance became a matter of fact. According to The History of Bedford, Somerset and Fulton Counties, Pennsylvania, there was a 'rude fortification' along the west bank of Sheaver's Creek to which the local settlers would flee when danger approached. The fort which was claimed to have stood on lands owned by Adam Shuss in 1884 was called Fort Defiance. The 'fact' of the matter is that Mr. Shuss was the sole provider of information on the fort ~ perhaps to garner historical importance to his own property. According to the Report of the Commission to Locate the Site of the Frontier Forts of Pennsylvania, referring to Fort Defiance: "The legendary and traditionary details of this locality are meagre, and notwithstanding that we have made an attempt to ascertain its true history, yet it leaves us in much doubt and uncertainty." This quote comes from Volume I in a section titled Fort Martin. The section details a fortified structure that was noted as "erected prior to the termination of the Revolutionary struggle." The so-called Fort Martin was stated to have existed on lands first settled by Judge [James] Martin, and at the time of the publication of the Report, owned by --- Whetstone. The author additionally noted: "The writer, from data at hand, cannot with any authority, give it the dignity of a fort. It doubtless was a mere blockhouse or rendezvous for the settlers in that vicinity and built with the private funds of the owner of the property, who, doubtless, was Mr. Martin." As has been discussed elsewhere in this volume, Fort Juniata, constructed during the Forbes Campaign in order to provide defense for supply trains during the process of being ferried across the Raystown Branch of the Juniata River, would have been located where the so-called Fort Martin was claimed to have stood in later years. The Fort at Juniata Crossing would have to have been located upstream from the present 'crossing' by US Route 30. The banks of the Juniata River at the present crossing are too steep, and the channel too narrow to permit Fort Juniata to have been spread out on both sides of the river at that location. And it is probable that James Martin chose that site on which to build his homestead / tavern since the Great Road crossed the river at that site. Vestigial memories of the Fort at Juniata Crossing more than likely provided the basis for the tradition that a fort had been located in the vicinity. Adam Shuss probably decided to appropriate those memories to his own property, creating the valiantly named Fort Defiance. In any case, despite the name, there exist no records to support any claim that such a 'Fort Defiance' existed or that it was ever attacked by Amerindians.

In the absence of public records, local traditions arise to fill gaps in the historical record. Since no one can prove them to be wrong, those traditions are accepted as truth. Each time that they are repeated, the traditions take on more legitimacy. Eventually, a tradition becomes a fact. That is how Fort Defiance became a matter of fact. According to The History of Bedford, Somerset and Fulton Counties, Pennsylvania, there was a 'rude fortification' along the west bank of Sheaver's Creek to which the local settlers would flee when danger approached. The fort which was claimed to have stood on lands owned by Adam Shuss in 1884 was called Fort Defiance. The 'fact' of the matter is that Mr. Shuss was the sole provider of information on the fort ~ perhaps to garner historical importance to his own property. According to the Report of the Commission to Locate the Site of the Frontier Forts of Pennsylvania, referring to Fort Defiance: "The legendary and traditionary details of this locality are meagre, and notwithstanding that we have made an attempt to ascertain its true history, yet it leaves us in much doubt and uncertainty." This quote comes from Volume I in a section titled Fort Martin. The section details a fortified structure that was noted as "erected prior to the termination of the Revolutionary struggle." The so-called Fort Martin was stated to have existed on lands first settled by Judge [James] Martin, and at the time of the publication of the Report, owned by --- Whetstone. The author additionally noted: "The writer, from data at hand, cannot with any authority, give it the dignity of a fort. It doubtless was a mere blockhouse or rendezvous for the settlers in that vicinity and built with the private funds of the owner of the property, who, doubtless, was Mr. Martin." As has been discussed elsewhere in this volume, Fort Juniata, constructed during the Forbes Campaign in order to provide defense for supply trains during the process of being ferried across the Raystown Branch of the Juniata River, would have been located where the so-called Fort Martin was claimed to have stood in later years. The Fort at Juniata Crossing would have to have been located upstream from the present 'crossing' by US Route 30. The banks of the Juniata River at the present crossing are too steep, and the channel too narrow to permit Fort Juniata to have been spread out on both sides of the river at that location. And it is probable that James Martin chose that site on which to build his homestead / tavern since the Great Road crossed the river at that site. Vestigial memories of the Fort at Juniata Crossing more than likely provided the basis for the tradition that a fort had been located in the vicinity. Adam Shuss probably decided to appropriate those memories to his own property, creating the valiantly named Fort Defiance. In any case, despite the name, there exist no records to support any claim that such a 'Fort Defiance' existed or that it was ever attacked by Amerindians.

![]() It is possible, though not substantiated by recorded fact that some families might have begun to settle in the vicinity of Bloody Run to form the basis of a village. But to state that a village actually existed along the Juniata River in the vicinity of the south end of Tussey Mountain in 1759 can only be the filling in of a blank in the absence of any verified facts.

It is possible, though not substantiated by recorded fact that some families might have begun to settle in the vicinity of Bloody Run to form the basis of a village. But to state that a village actually existed along the Juniata River in the vicinity of the south end of Tussey Mountain in 1759 can only be the filling in of a blank in the absence of any verified facts.

![]() The source of the name Bloody Run has puzzled local historians and others for many decades. And it will be dealt with in another section of this website. At this time I will offer my own suggestion.

The source of the name Bloody Run has puzzled local historians and others for many decades. And it will be dealt with in another section of this website. At this time I will offer my own suggestion.

![]() People living in the 2020's, especially Americans, will most likely associate a word such as 'bloody' with the things with which the word is associated at the present time. People in 1906 probably associated the word 'bloody' with the things with which the word was associated in the year 1906. People living in the year 1843, in all probability, would have associated the word 'bloody' with the things with which the word was associated in the year 1843. And it is quite likely that the people in the four years between 1755 and 1759 would have associated the word 'bloody' with the swear or 'cuss' word which meant undesirable or condemned. Even at the present time, despite its non-usage in the United States, the word is used by the British as an expletive, or swear word. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word appeared in print in 1785 with that meaning. And it is not too outrageous to assume that the word ~ used as an expletive ~ was in common usage long before it appeared in print. Too often people, in their own time period, refuse to acknowledge that things weren't always the way that they know them. Earlier attempts to decipher the reason for the stream being called 'Bloody' Run were based on making some sort of association with actual physical blood causing a change in the water's physical appearance. After making that assumption, the American historian looked for an event that could contribute to physical blood changing the physical appearance of the stream's water. Although no contemporary record could be found to explain the name, any event, anywhere in the general region, and at any time within ten years of the first known recording of the name that resulted in the spilling of physical blood was appropriated for the explanation.

People living in the 2020's, especially Americans, will most likely associate a word such as 'bloody' with the things with which the word is associated at the present time. People in 1906 probably associated the word 'bloody' with the things with which the word was associated in the year 1906. People living in the year 1843, in all probability, would have associated the word 'bloody' with the things with which the word was associated in the year 1843. And it is quite likely that the people in the four years between 1755 and 1759 would have associated the word 'bloody' with the swear or 'cuss' word which meant undesirable or condemned. Even at the present time, despite its non-usage in the United States, the word is used by the British as an expletive, or swear word. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word appeared in print in 1785 with that meaning. And it is not too outrageous to assume that the word ~ used as an expletive ~ was in common usage long before it appeared in print. Too often people, in their own time period, refuse to acknowledge that things weren't always the way that they know them. Earlier attempts to decipher the reason for the stream being called 'Bloody' Run were based on making some sort of association with actual physical blood causing a change in the water's physical appearance. After making that assumption, the American historian looked for an event that could contribute to physical blood changing the physical appearance of the stream's water. Although no contemporary record could be found to explain the name, any event, anywhere in the general region, and at any time within ten years of the first known recording of the name that resulted in the spilling of physical blood was appropriated for the explanation.

![]() What has been overlooked is the fact that the name first appeared in an English military context (i.e. the 1759 Accounts of Pack Horses) and the English soldiers might simply have referred to the stream in a somewhat derogatory, but common manner. Instead of calling it the D-a-m-n-e-d Run, they might have used the word 'bloody' simply as the common alternative expletive that it was, and still is, in Britain.

What has been overlooked is the fact that the name first appeared in an English military context (i.e. the 1759 Accounts of Pack Horses) and the English soldiers might simply have referred to the stream in a somewhat derogatory, but common manner. Instead of calling it the D-a-m-n-e-d Run, they might have used the word 'bloody' simply as the common alternative expletive that it was, and still is, in Britain.

![]() As plausible as any of the other explanations is the possibility that as the English army of the Forbes campaign headed westward, one of the soldiers at the front of the line might have slipped and fallen into the small stream. His fellow soldiers might have laughed at the thoroughly wet man's misfortunate as he cursed the 'damned stream' in the jargon of his native homeland. The sarcastic warning, "Watch that you don't fall in the bloody run!" might have been passed down the line. This explanation is definitely not one that is quixotic, or heroic, as the result of a battle or slaughter of beasts, but it as plausible as any of the other ones.

As plausible as any of the other explanations is the possibility that as the English army of the Forbes campaign headed westward, one of the soldiers at the front of the line might have slipped and fallen into the small stream. His fellow soldiers might have laughed at the thoroughly wet man's misfortunate as he cursed the 'damned stream' in the jargon of his native homeland. The sarcastic warning, "Watch that you don't fall in the bloody run!" might have been passed down the line. This explanation is definitely not one that is quixotic, or heroic, as the result of a battle or slaughter of beasts, but it as plausible as any of the other ones.

![]() Nothing is mentioned in contemporary public documents about Bloody Run until the year 1787. On 07 March of that year, Michael Barndollar, originally from Philadelphia, but in the 1780's living in Frederick County, Maryland, purchased a tract of land encompassing a little over four hundred acres in Colerain Township from John Musser of Lancaster. Musser was apparently one of many absentee land speculators who stayed down east but bought up large portions of land in the frontier, so that they could later divide them and sell smaller tracts to multiple buyers.

Nothing is mentioned in contemporary public documents about Bloody Run until the year 1787. On 07 March of that year, Michael Barndollar, originally from Philadelphia, but in the 1780's living in Frederick County, Maryland, purchased a tract of land encompassing a little over four hundred acres in Colerain Township from John Musser of Lancaster. Musser was apparently one of many absentee land speculators who stayed down east but bought up large portions of land in the frontier, so that they could later divide them and sell smaller tracts to multiple buyers.

![]() The document made out between John Musser as grantor and Michael Barndollar as grantee was actually a mortgage with certain bonds due over a period of time. The date of instrument was 07 March 1787 and the last bond was due on 01 March 1794. That could explain why it was not until 1795 that Mr. Barndollar laid out a town within the tract. He did not clearly own the tract until 1794.

The document made out between John Musser as grantor and Michael Barndollar as grantee was actually a mortgage with certain bonds due over a period of time. The date of instrument was 07 March 1787 and the last bond was due on 01 March 1794. That could explain why it was not until 1795 that Mr. Barndollar laid out a town within the tract. He did not clearly own the tract until 1794.

![]() Michael Barndollar laid out a town plat on 15 June 1795. He named it Waynesburg. The name, according to some historians, was in honor of 'Mad' Anthony Wayne, a hero of the American Revolutionary War. But according to a pamphlet produced in 1971, it was stated that the name was bestowed in honor of a man named George Wayne. Unfortunately for an accurate history of Everett Borough, no one knows who George Wayne was. The name does not appear in the published Pennsylvania Archives; he apparently was not a notable figure in Pennsylvania's historical record. Also, the original 1795 survey of Waynesburg is no longer extant. It would appear that the town was laid out with lots flanking a primary street, named Main Street, which lay parallel to the original Forbes Road. Local historians currently believe that Foundry Street defines the path of Forbes Road. Since Main Street lies parallel, one block to the south of Foundry Street, it suggests that Michael Barndollar wanted to avoid the heavily traveled Forbes/Great Road.

Michael Barndollar laid out a town plat on 15 June 1795. He named it Waynesburg. The name, according to some historians, was in honor of 'Mad' Anthony Wayne, a hero of the American Revolutionary War. But according to a pamphlet produced in 1971, it was stated that the name was bestowed in honor of a man named George Wayne. Unfortunately for an accurate history of Everett Borough, no one knows who George Wayne was. The name does not appear in the published Pennsylvania Archives; he apparently was not a notable figure in Pennsylvania's historical record. Also, the original 1795 survey of Waynesburg is no longer extant. It would appear that the town was laid out with lots flanking a primary street, named Main Street, which lay parallel to the original Forbes Road. Local historians currently believe that Foundry Street defines the path of Forbes Road. Since Main Street lies parallel, one block to the south of Foundry Street, it suggests that Michael Barndollar wanted to avoid the heavily traveled Forbes/Great Road.

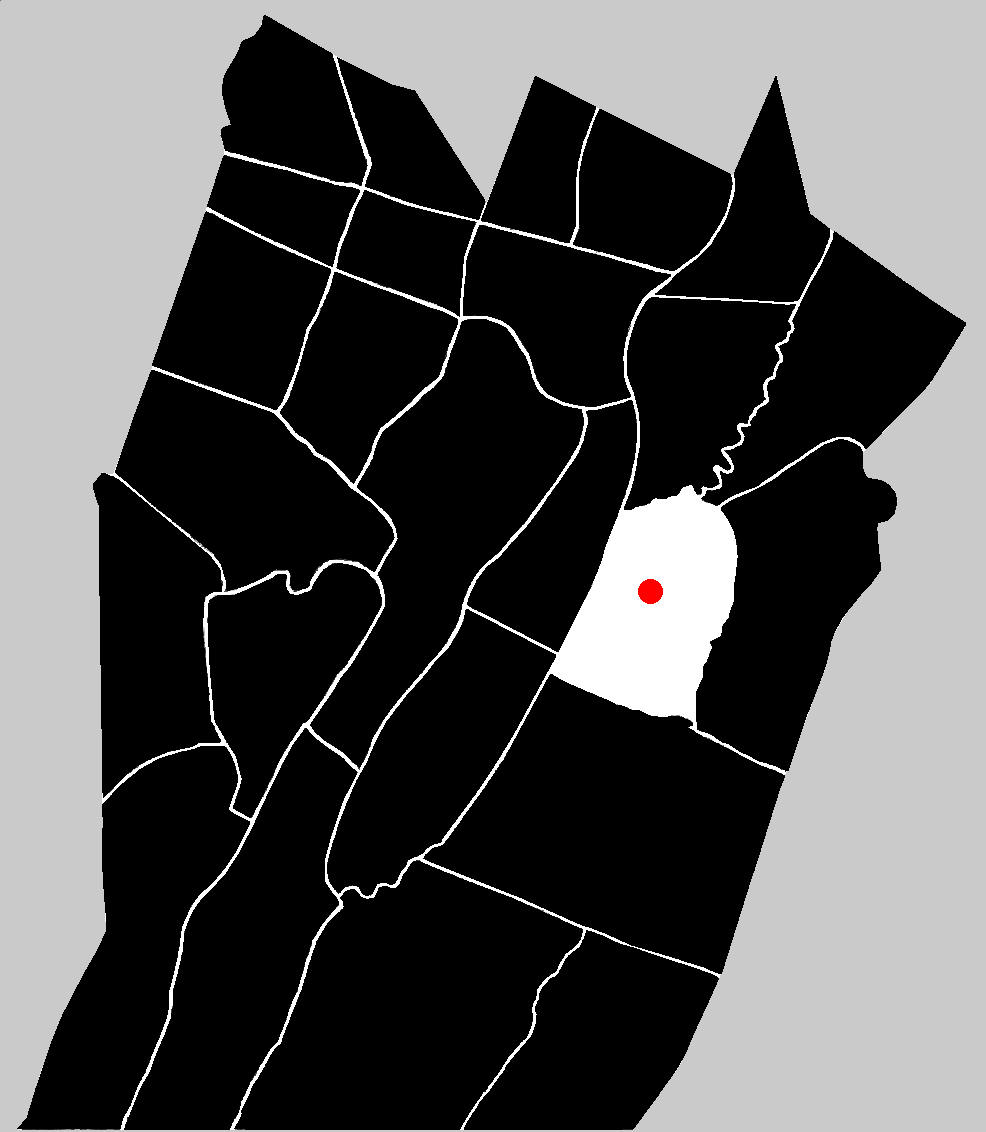

![]() In spite of Michael Barndollar's desire for his village to be named Waynsburg, most people called it Bloody Run. After his death, Michael's wishes were ignored when the townsfolk decided to incorporate into a borough. On 22 November 1860, the Court of the Quarter Sessions of the Peace for Bedford County granted incorporation status to the village of Bloody Run, thereby making it the third village in Bedford County to become a borough (after Bedford in 1795 and Schellsburg in 1838). A petition to incorporate the town was submitted to the Court on 30 April 1860 by twenty-six residents.

In spite of Michael Barndollar's desire for his village to be named Waynsburg, most people called it Bloody Run. After his death, Michael's wishes were ignored when the townsfolk decided to incorporate into a borough. On 22 November 1860, the Court of the Quarter Sessions of the Peace for Bedford County granted incorporation status to the village of Bloody Run, thereby making it the third village in Bedford County to become a borough (after Bedford in 1795 and Schellsburg in 1838). A petition to incorporate the town was submitted to the Court on 30 April 1860 by twenty-six residents.

![]() In 1873, a movement was started to change the name of the borough of Bloody Run. Those in favor of a change felt that the name, by which the borough had been incorporated just thirteen years earlier, was offensive and an embarrassment. The name 'Everett' was chosen in honor of Edward Everett, a politician from Massachusetts and an orator who advocated the avoidance of war at the start of the Civil War. Edward Everett is perhaps most famous for being the keynote speaker at the dedication of the cemetery at Gettysburg, whose hour long speech is practically forgotten in favor of President Abraham Lincoln's short comments. The name of the borough was officially changed on 13 February 1873 to 'Everett.'

In 1873, a movement was started to change the name of the borough of Bloody Run. Those in favor of a change felt that the name, by which the borough had been incorporated just thirteen years earlier, was offensive and an embarrassment. The name 'Everett' was chosen in honor of Edward Everett, a politician from Massachusetts and an orator who advocated the avoidance of war at the start of the Civil War. Edward Everett is perhaps most famous for being the keynote speaker at the dedication of the cemetery at Gettysburg, whose hour long speech is practically forgotten in favor of President Abraham Lincoln's short comments. The name of the borough was officially changed on 13 February 1873 to 'Everett.'