![]() Bloody Run was first mentioned in a listing of pack horses that died or were stolen during the Forbes Campaign. A List of the Different Bregads of Horses Killed & Taken by the Enemy was compiled at some time in 1759 (the exact date is not stated) by Callender and Hughes. Captain Robert Callender and Mr. Barnabas Hughes were in charge of the divisions of pack horses carrying the supplies during Forbes Campaign. An inventory of the horses was taken near the end of the year 1759. William White was in charge of Brigade #4. He reported that one horse 'gave out' (i.e. died from exhaustion) "at Bloody Run by ye Officer making me drive two hard."

Bloody Run was first mentioned in a listing of pack horses that died or were stolen during the Forbes Campaign. A List of the Different Bregads of Horses Killed & Taken by the Enemy was compiled at some time in 1759 (the exact date is not stated) by Callender and Hughes. Captain Robert Callender and Mr. Barnabas Hughes were in charge of the divisions of pack horses carrying the supplies during Forbes Campaign. An inventory of the horses was taken near the end of the year 1759. William White was in charge of Brigade #4. He reported that one horse 'gave out' (i.e. died from exhaustion) "at Bloody Run by ye Officer making me drive two hard."

![]() Many and varied 'stopping places' existed along the Forbes Road during the campaign to capture Fort Duquesne from the French. The stopping places included anything from proper (i.e. British Royal Army approved) fortifications, such as Fort Lyttelton and Fort Bedford to redoubt protected sites such as the Shawnee Cabins and Fort Dewart to unfortified but commonly known landmarks, such as Dunnings [Crossing], the Snake Spring and Bloody Run ~ all three of which were included in the Accounts of Pack Horses reported by Callender and Hughes in 1759. There exists no record in either the transcribed papers of Colonel Henry Bouquet, the papers of General John Forbes or the published Pennsylvania Archives to suggest that any type of settlement or village existed at any of the three landmarks last noted. They were probably well known locales where horses could be rested, and more importantly watered and refreshed, before moving on to the next point along the Communication, the series of fortifications along the route rom Carlisle to the Forks of the Ohio.

Many and varied 'stopping places' existed along the Forbes Road during the campaign to capture Fort Duquesne from the French. The stopping places included anything from proper (i.e. British Royal Army approved) fortifications, such as Fort Lyttelton and Fort Bedford to redoubt protected sites such as the Shawnee Cabins and Fort Dewart to unfortified but commonly known landmarks, such as Dunnings [Crossing], the Snake Spring and Bloody Run ~ all three of which were included in the Accounts of Pack Horses reported by Callender and Hughes in 1759. There exists no record in either the transcribed papers of Colonel Henry Bouquet, the papers of General John Forbes or the published Pennsylvania Archives to suggest that any type of settlement or village existed at any of the three landmarks last noted. They were probably well known locales where horses could be rested, and more importantly watered and refreshed, before moving on to the next point along the Communication, the series of fortifications along the route rom Carlisle to the Forks of the Ohio.

![]() The origin of the name of Bloody Run is not revealed in any documentation that was published contemporary with the events during which it was first employed. As noted above, the name first appeared in the 1759 Accounts of Pack Horses, and that report's authors, Callender and Hughes, did not feel that there was any necessity to attach any modifying or identifying words to the name. If there had been a settlement or some sort of fortification in the vicinity, the entry might have read Bloody Run Village or Bloody Run Redoubt, but no such modifier was included and so the only assumption that can be made is that the name referred to the waterway itself, and not to some landmark associated with the waterway. Now, the origin of the name Bloody Run has been questioned over the years. And historians have attempted to explain it by a number of theories, none of which can be verified by any publicly documented sources.

The origin of the name of Bloody Run is not revealed in any documentation that was published contemporary with the events during which it was first employed. As noted above, the name first appeared in the 1759 Accounts of Pack Horses, and that report's authors, Callender and Hughes, did not feel that there was any necessity to attach any modifying or identifying words to the name. If there had been a settlement or some sort of fortification in the vicinity, the entry might have read Bloody Run Village or Bloody Run Redoubt, but no such modifier was included and so the only assumption that can be made is that the name referred to the waterway itself, and not to some landmark associated with the waterway. Now, the origin of the name Bloody Run has been questioned over the years. And historians have attempted to explain it by a number of theories, none of which can be verified by any publicly documented sources.

![]() The most popular local tradition is that the stream gained its name by being filled with the blood of many men killed in an epic battle between EuroAmericans and Amerindians. So when did that epic battle, in which enough men's bodies would have been hacked and sliced so that their blood would overfill the water in the stream to make it appear 'bloody', take place?

The most popular local tradition is that the stream gained its name by being filled with the blood of many men killed in an epic battle between EuroAmericans and Amerindians. So when did that epic battle, in which enough men's bodies would have been hacked and sliced so that their blood would overfill the water in the stream to make it appear 'bloody', take place?

![]() One of the theories regarding the origin of the name Bloody Run came from an article printed in a London newspaper. The article stated:

One of the theories regarding the origin of the name Bloody Run came from an article printed in a London newspaper. The article stated:

![]() By advices from Philadelphia we learn that the convoy of eighty horses loaded with goods, chiefly on his Majesty's account, as presents to the Indians, and part on account of Indian traders, were surprised in a narrow and dangerous defile in the mountains by a body of armed men. A number of horses were killed, some lives were lost, and the whole of the goods were carried away by the plunderers. The rivulet was dyed with blood, and run into the settlement below, carrying with it the stain of crime upon its surface. This convoy was intended for Pittsburg; as there can be no long continuance of peace, without such strong demonstrations of friendship towards the Indians. The King's troops from Fort Loudon marched against the depredators, seized them, but were again rescued by superior force. Some soldiers carried some straglers, whom they apprehended, into the Fort; but their friends came to their rescue and compelled the garrison to give up the prisoners. We understand, however, that many of the rioters were bound over for their appearance at court.

By advices from Philadelphia we learn that the convoy of eighty horses loaded with goods, chiefly on his Majesty's account, as presents to the Indians, and part on account of Indian traders, were surprised in a narrow and dangerous defile in the mountains by a body of armed men. A number of horses were killed, some lives were lost, and the whole of the goods were carried away by the plunderers. The rivulet was dyed with blood, and run into the settlement below, carrying with it the stain of crime upon its surface. This convoy was intended for Pittsburg; as there can be no long continuance of peace, without such strong demonstrations of friendship towards the Indians. The King's troops from Fort Loudon marched against the depredators, seized them, but were again rescued by superior force. Some soldiers carried some straglers, whom they apprehended, into the Fort; but their friends came to their rescue and compelled the garrison to give up the prisoners. We understand, however, that many of the rioters were bound over for their appearance at court.

![]() The foregoing account that was printed in the English newspaper bore the dateline: Council Chambers, London, June 21, 1765. The incident was eventually identified as having taken place along the eastern slope of Sideling Hill. The account was transcribed in 1846, by I. Daniel Rupp, in his The History and Topography of Dauphin, Cumberland, Franklin, Bedford, Adams, and Perry Counties. It was also referenced by U. J. Jones in his History of the Early Settlement of the Juniata Valley, published in 1855. Jones attributed the incident to James Smith and his Black Boys. The simple matter that the incident related in the newspaper was dated to the year 1765, whereas the name of Bloody Run had been mentioned six years earlier in 1759, was apparently overlooked by Rupp and Jones.

The foregoing account that was printed in the English newspaper bore the dateline: Council Chambers, London, June 21, 1765. The incident was eventually identified as having taken place along the eastern slope of Sideling Hill. The account was transcribed in 1846, by I. Daniel Rupp, in his The History and Topography of Dauphin, Cumberland, Franklin, Bedford, Adams, and Perry Counties. It was also referenced by U. J. Jones in his History of the Early Settlement of the Juniata Valley, published in 1855. Jones attributed the incident to James Smith and his Black Boys. The simple matter that the incident related in the newspaper was dated to the year 1765, whereas the name of Bloody Run had been mentioned six years earlier in 1759, was apparently overlooked by Rupp and Jones.

![]() The pamphlet prepared 'in connection with the Bedford County Bicentennial' in 1971 stated that "In attempting to dissuade a group of traders from carrying goods and war-like supplies to the Indians ~ and thus endangering the lives of the white settlers ~ a group of 50 men under William Duffield disguised themselves as Indians and, when the traders came along, shot their horses. There were 70 horses in the pack train and the blood of those that were massacred tinged the waters of the run to a ruddy hue." The author of the narrative then made the statement that "James Smith, an intrepid warrior of the period before the Revolution in telling the story, lays the scene of the skirmish at Rays Hill, but, since there was no settlement there at that time, it is believed that the traders were waylaid in the vicinity of Everett." The latter statement, in attempting to justify the 'fact' that the incident could not have occurred at Rays Hill because there was no settlement there at the time, overlooked the fact that there likewise was no settlement at 'Everett' at that time. While it made for interesting reading in the little pamphlet, the story missed the truth. It was derived from the 1843 volume Historical Collections of the State of Pennsylvania, by Sherman Day. Mr. Day derived his information from An Account of the Remarkable Coincidences in the Life and Travels of Col. James Smith, published in 1799. A major problem with the use of the story of Duffield and his fifty men, by Smith and Day, was that the narrative itself includes the statement that Duffield and his fifty men met the traders "where Mercersburg now stands". And the narrative, as presented by Smith, and later Day, stated that Duffield and his men left the traders proceed, and it was then Smith and ten of his 'Black Boys' who actually waylaid the pack train. Smith stated that after crossing over North Mountain, his men stopped the traders near Sidelong [sic] Hill. He mentioned nothing about seventy horses being killed. But most importantly, Smith stated that the incident took place around the first of March 1765 ~ six years after the first use of the name, Bloody Run.

The pamphlet prepared 'in connection with the Bedford County Bicentennial' in 1971 stated that "In attempting to dissuade a group of traders from carrying goods and war-like supplies to the Indians ~ and thus endangering the lives of the white settlers ~ a group of 50 men under William Duffield disguised themselves as Indians and, when the traders came along, shot their horses. There were 70 horses in the pack train and the blood of those that were massacred tinged the waters of the run to a ruddy hue." The author of the narrative then made the statement that "James Smith, an intrepid warrior of the period before the Revolution in telling the story, lays the scene of the skirmish at Rays Hill, but, since there was no settlement there at that time, it is believed that the traders were waylaid in the vicinity of Everett." The latter statement, in attempting to justify the 'fact' that the incident could not have occurred at Rays Hill because there was no settlement there at the time, overlooked the fact that there likewise was no settlement at 'Everett' at that time. While it made for interesting reading in the little pamphlet, the story missed the truth. It was derived from the 1843 volume Historical Collections of the State of Pennsylvania, by Sherman Day. Mr. Day derived his information from An Account of the Remarkable Coincidences in the Life and Travels of Col. James Smith, published in 1799. A major problem with the use of the story of Duffield and his fifty men, by Smith and Day, was that the narrative itself includes the statement that Duffield and his fifty men met the traders "where Mercersburg now stands". And the narrative, as presented by Smith, and later Day, stated that Duffield and his men left the traders proceed, and it was then Smith and ten of his 'Black Boys' who actually waylaid the pack train. Smith stated that after crossing over North Mountain, his men stopped the traders near Sidelong [sic] Hill. He mentioned nothing about seventy horses being killed. But most importantly, Smith stated that the incident took place around the first of March 1765 ~ six years after the first use of the name, Bloody Run.

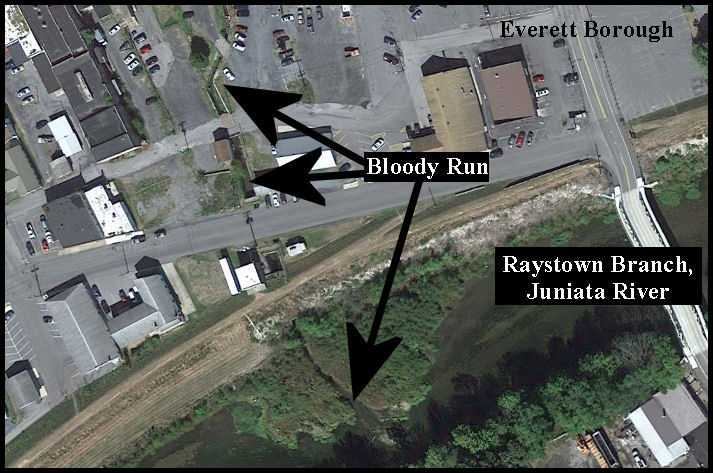

![]() The History of Bedford, Somerset and Fulton Counties, Pennsylvania noted the general attribution of the name to the 1765 newspaper account, but pointed out the absurdity of the incident at Sideling Hill providing a name for a waterway that was twenty-some miles distant. Instead, that volume presented an alternative source for the name. It was suggested that the name was derived from an incident that occurred in 1768 in which it was stated "that when Forbe's army passed over the old military road in 1768, a halt was made near the spring, and that several cattle were slaughtered here to supply the army with meat." The most blatant error with this story is associating anything that occurred in the year 1768 with the Forbes Campaign of 1758-59. Secondly, the implication was that the blood from the slaughtered cows dyed the stream waters red. But where exactly is the spring? It is a little over a mile north of the Juniata River into which it empties. It is assumed that Forbes Road lay somewhat on the course followed by present-day US Route 30 (which is named Main Street in the borough). Would the British Army victualers have left the already cleared roadway, to lead the cattle to a spot a mile away, in order to slaughter them right at the spring, only to pollute the entire stream? What the author of that statement also apparently failed to notice was that, if the date of 1768 was correct, the incident would have occurred nine years after the stream was named.

The History of Bedford, Somerset and Fulton Counties, Pennsylvania noted the general attribution of the name to the 1765 newspaper account, but pointed out the absurdity of the incident at Sideling Hill providing a name for a waterway that was twenty-some miles distant. Instead, that volume presented an alternative source for the name. It was suggested that the name was derived from an incident that occurred in 1768 in which it was stated "that when Forbe's army passed over the old military road in 1768, a halt was made near the spring, and that several cattle were slaughtered here to supply the army with meat." The most blatant error with this story is associating anything that occurred in the year 1768 with the Forbes Campaign of 1758-59. Secondly, the implication was that the blood from the slaughtered cows dyed the stream waters red. But where exactly is the spring? It is a little over a mile north of the Juniata River into which it empties. It is assumed that Forbes Road lay somewhat on the course followed by present-day US Route 30 (which is named Main Street in the borough). Would the British Army victualers have left the already cleared roadway, to lead the cattle to a spot a mile away, in order to slaughter them right at the spring, only to pollute the entire stream? What the author of that statement also apparently failed to notice was that, if the date of 1768 was correct, the incident would have occurred nine years after the stream was named.

![]() A final suggestion for the name, Bloody Run comes from a tradition that a battle was fought in the vicinity of the stream between Amerindians and British Army soldiers. According to the unverified story, the soldiers were part of the Burd's Road project in 1755, and they were attacked by a party of Amerindians. The story was popularized by J. Warren Smouse in his History of the Smouse Family of America, published in 1908. The story was then quoted by other genealogists, and as it was repeated, it was believed. According to the Smouse story: "During the French and Indian War he [John Smouse] and Christian Miller were in the employ of the Government. They were hauling supplies and helped to cut a road from Carlisle to Fort Bedford. He was present with his team [of horses] when that fierce battle was fought at Bloody Run, now Everett, PA. He was one of eighteen men who with Captain Stone rescued six prisoners that were to be burned by the Indians. . ." Absolutely no record of any such incident was recorded and maintained in the papers that would be published as the Pennsylvania Archives. Also, the only man named 'Captain Stone' associated with the French and Indian War was killed during 'the Action on the Banks of the Monongahela the 9th Day of July, 1755.' Although historians have stated with authority that the incident indeed took place, there simply is no way to prove it with documented facts. Any 'fierce battle' should surely merit at least being mentioned once in a military commander's papers.

A final suggestion for the name, Bloody Run comes from a tradition that a battle was fought in the vicinity of the stream between Amerindians and British Army soldiers. According to the unverified story, the soldiers were part of the Burd's Road project in 1755, and they were attacked by a party of Amerindians. The story was popularized by J. Warren Smouse in his History of the Smouse Family of America, published in 1908. The story was then quoted by other genealogists, and as it was repeated, it was believed. According to the Smouse story: "During the French and Indian War he [John Smouse] and Christian Miller were in the employ of the Government. They were hauling supplies and helped to cut a road from Carlisle to Fort Bedford. He was present with his team [of horses] when that fierce battle was fought at Bloody Run, now Everett, PA. He was one of eighteen men who with Captain Stone rescued six prisoners that were to be burned by the Indians. . ." Absolutely no record of any such incident was recorded and maintained in the papers that would be published as the Pennsylvania Archives. Also, the only man named 'Captain Stone' associated with the French and Indian War was killed during 'the Action on the Banks of the Monongahela the 9th Day of July, 1755.' Although historians have stated with authority that the incident indeed took place, there simply is no way to prove it with documented facts. Any 'fierce battle' should surely merit at least being mentioned once in a military commander's papers.

![]() A somewhat plausible source of the name might actually lie in the fact that the high iron content in the stream causes the water to appear reddish (actually more orange-ish) at times. There are many streams throughout the region whose water is so laden with iron that it stains the rocks. Anyone who experiences the ruddy color of the water in a stream with high iron content for the first time would probably associate it with blood. This source of the name was suggested by David G. Agnew in A History of Everett."

A somewhat plausible source of the name might actually lie in the fact that the high iron content in the stream causes the water to appear reddish (actually more orange-ish) at times. There are many streams throughout the region whose water is so laden with iron that it stains the rocks. Anyone who experiences the ruddy color of the water in a stream with high iron content for the first time would probably associate it with blood. This source of the name was suggested by David G. Agnew in A History of Everett."

![]() One final suggestion should be made before leaving the subject of the name of Bloody Run. Larry D. Smith, in his "Bedford County, Pennsylvania ~ Two and One-Half Centuries in the Making" proposed this alternative origin of the name. People living in the year 2021 will most likely associate a word such as 'bloody' with the things with which the word is associated in 2021. People in 1906 probably associated the word 'bloody' with the things with which the word was associated in the year 1906. People living in the year 1843, in all probability, would have associated the word 'bloody' with the things with which the word was associated in the year 1843. And it is quite likely that the people in the four years between 1755 and 1759 would have associated the word 'bloody' with the swear or 'cuss' word which meant undesirable or condemned. Even at the present-time, despite its non-usage in the United States, the word is used by the British as an expletive, or swear word. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word appeared in print in 1785 with that meaning. And it is not too outrageous to assume that the word ~ used as an expletive ~ was in common usage long before it appeared in print. Too often people, in their own time period, refuse to acknowledge that things weren't always the way that they know them. Earlier attempts to decipher the reason for the stream being called 'Bloody' Run were based on making some sort of association with actual physical blood causing a change in the water's physical appearance. After making that assumption, the American historian looked for an event that could contribute to physical blood changing the physical appearance of the stream's water. Although no contemporary record could be found to explain the name, any event, anywhere in the general region, and at any time within ten years of the first known recording of the name that resulted in the spilling of physical blood was appropriated for the explanation.

One final suggestion should be made before leaving the subject of the name of Bloody Run. Larry D. Smith, in his "Bedford County, Pennsylvania ~ Two and One-Half Centuries in the Making" proposed this alternative origin of the name. People living in the year 2021 will most likely associate a word such as 'bloody' with the things with which the word is associated in 2021. People in 1906 probably associated the word 'bloody' with the things with which the word was associated in the year 1906. People living in the year 1843, in all probability, would have associated the word 'bloody' with the things with which the word was associated in the year 1843. And it is quite likely that the people in the four years between 1755 and 1759 would have associated the word 'bloody' with the swear or 'cuss' word which meant undesirable or condemned. Even at the present-time, despite its non-usage in the United States, the word is used by the British as an expletive, or swear word. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word appeared in print in 1785 with that meaning. And it is not too outrageous to assume that the word ~ used as an expletive ~ was in common usage long before it appeared in print. Too often people, in their own time period, refuse to acknowledge that things weren't always the way that they know them. Earlier attempts to decipher the reason for the stream being called 'Bloody' Run were based on making some sort of association with actual physical blood causing a change in the water's physical appearance. After making that assumption, the American historian looked for an event that could contribute to physical blood changing the physical appearance of the stream's water. Although no contemporary record could be found to explain the name, any event, anywhere in the general region, and at any time within ten years of the first known recording of the name that resulted in the spilling of physical blood was appropriated for the explanation.

![]() What has been overlooked is the fact that the name first appeared in an English military context (i.e. the 1759 Accounts of Pack Horses) and the English soldiers might simply have referred to the stream in a somewhat derogatory, but common manner. Instead of calling it the D-a-m-n-e-d Run, they might have used the word 'bloody' simply as the common alternative expletive that it was, and still is, in Britain.

What has been overlooked is the fact that the name first appeared in an English military context (i.e. the 1759 Accounts of Pack Horses) and the English soldiers might simply have referred to the stream in a somewhat derogatory, but common manner. Instead of calling it the D-a-m-n-e-d Run, they might have used the word 'bloody' simply as the common alternative expletive that it was, and still is, in Britain.

![]() As plausible as any of the foregoing explanations is the possibility that as the English army of the Forbes campaign headed westward, one of the soldiers at the front of the line might have slipped and fallen into the small stream. His fellow soldiers might have laughed at the thoroughly wet man's misfortunate as he cursed the 'damned stream' in the jargon of his native homeland. The sarcastic warning, "Watch that you don't fall in the bloody run!" might have been passed down the line. This explanation is definitely not one that is quixotic, or heroic, as the result of a battle or slaughter of beasts, but it as plausible as any of the other ones.

As plausible as any of the foregoing explanations is the possibility that as the English army of the Forbes campaign headed westward, one of the soldiers at the front of the line might have slipped and fallen into the small stream. His fellow soldiers might have laughed at the thoroughly wet man's misfortunate as he cursed the 'damned stream' in the jargon of his native homeland. The sarcastic warning, "Watch that you don't fall in the bloody run!" might have been passed down the line. This explanation is definitely not one that is quixotic, or heroic, as the result of a battle or slaughter of beasts, but it as plausible as any of the other ones.