![]() The first court house to serve the needs of Bedford County was constructed of logs. It stood on the northeast corner of the Square in the town of Bedford on Lot #6 as laid out by John Lukens in 1766. A log jail was constructed on the unused half of Lot #7 adjacent to and along the south side of the court house. It consisted of only one story. The jail also consisted of a single story with only a trap door in the roof through which a ladder would be inserted to either have a prisoner put in or taken out of the building.

The first court house to serve the needs of Bedford County was constructed of logs. It stood on the northeast corner of the Square in the town of Bedford on Lot #6 as laid out by John Lukens in 1766. A log jail was constructed on the unused half of Lot #7 adjacent to and along the south side of the court house. It consisted of only one story. The jail also consisted of a single story with only a trap door in the roof through which a ladder would be inserted to either have a prisoner put in or taken out of the building.

![]() The log court house was constructed in the summer of 1771 after the new county was officially erected out of Cumberland County. After the first (March) Court of General Quarter Sesssion of the Peace and Gaol was held in Henry Wertz's house, the courts were held in the log court house.

The log court house was constructed in the summer of 1771 after the new county was officially erected out of Cumberland County. After the first (March) Court of General Quarter Sesssion of the Peace and Gaol was held in Henry Wertz's house, the courts were held in the log court house.

![]() Between 1771 and 1774, a new court house constructed of stone was built on the northwest corner of the Square, opposite to the log one. This new stone court house consisted of two and one-half stories. The ground floor was divided into two rooms, The one served as the jail while the other served as the jailor's living quarters. It is claimed that a dungeon was dug in one dark corner of the jail. The second floor's single large room served as the court room for the Court of General Quarter Session of the Peace and Gail. The court room was reached by an exterior set of steps. In one corner was a set of steps going up to the third, or attic, story. The small room in the third floor served as the court room for the Court of Oyer and Terminer and other Petty courts.

Between 1771 and 1774, a new court house constructed of stone was built on the northwest corner of the Square, opposite to the log one. This new stone court house consisted of two and one-half stories. The ground floor was divided into two rooms, The one served as the jail while the other served as the jailor's living quarters. It is claimed that a dungeon was dug in one dark corner of the jail. The second floor's single large room served as the court room for the Court of General Quarter Session of the Peace and Gail. The court room was reached by an exterior set of steps. In one corner was a set of steps going up to the third, or attic, story. The small room in the third floor served as the court room for the Court of Oyer and Terminer and other Petty courts.

![]() The stone court house did not have room for the various officers of the court system, such as the Prothontary, the Register of Wills and Recorder of Deeds and the Clerk of Courts. They took up offices in other buildings throughout the town. When Arthur St. Clair served as the Prothontary and Clerk of Courts, he had an office space in the cellar of the small stone house built by Thomas Smith (later known as the Espy House) on the north side of Pitt Street.

The stone court house did not have room for the various officers of the court system, such as the Prothontary, the Register of Wills and Recorder of Deeds and the Clerk of Courts. They took up offices in other buildings throughout the town. When Arthur St. Clair served as the Prothontary and Clerk of Courts, he had an office space in the cellar of the small stone house built by Thomas Smith (later known as the Espy House) on the north side of Pitt Street.

![]() The stone court house was in use between 1774 and 1829. In 1826 work began on a new brick court house. It was built on the southwest corner of the Square under the direction of local architect, Solomon Filler. The new brick building was not completed until 1829, although it is believed that some of the employees began to work in their offices in the new building during 1828.

The stone court house was in use between 1774 and 1829. In 1826 work began on a new brick court house. It was built on the southwest corner of the Square under the direction of local architect, Solomon Filler. The new brick building was not completed until 1829, although it is believed that some of the employees began to work in their offices in the new building during 1828.

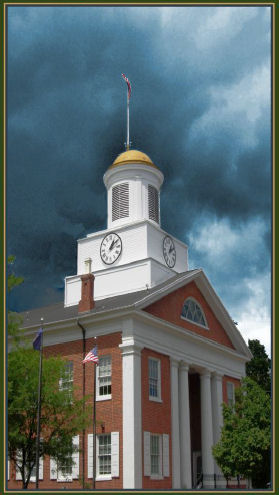

![]() The construction crew led by Solomon Filler produced a three-storey structure with exterior walls of red brick, and wood treatments in the Greek Revival style. There is a basement, first floor and second floor. There is no attic room, per se since the second floor courtroom has a curved 'cathedral' ceiling. Only a small crawl space is above the second floor ceiling. The structure measured fifty-four feet in width and sixty-five and three-quarter feet in length. Combined with an addition constructed in 1876 (to accommodate large walk-in safes for the Prothonotary and Register and Recorder's offices), the length was increased to ninety-two feet. Viewed from the outside, there are two levels of windows; the 'third' floor would have referred to the basement level.

The construction crew led by Solomon Filler produced a three-storey structure with exterior walls of red brick, and wood treatments in the Greek Revival style. There is a basement, first floor and second floor. There is no attic room, per se since the second floor courtroom has a curved 'cathedral' ceiling. Only a small crawl space is above the second floor ceiling. The structure measured fifty-four feet in width and sixty-five and three-quarter feet in length. Combined with an addition constructed in 1876 (to accommodate large walk-in safes for the Prothonotary and Register and Recorder's offices), the length was increased to ninety-two feet. Viewed from the outside, there are two levels of windows; the 'third' floor would have referred to the basement level.

![]() The facade on the structure's east end faces Juliana Street. Two square columns built into the red brick wall, known as pilasters, flank either side of two round, free-standing, Doric-style columns, all of which appear to hold up the lintel, frieze and pediment. The two central round columns stand in front of a recessed front-entrance portico. Despite their carved-stone-like appearance, the round columns are actually composed of thin, four-inch wide strips of wood positioned like barrel staves and glued together. Although a round 'bull's-eye' window was a standard element for the Greek Revival style, a half circle window accents the portion of brick wall above the frieze in the Bedford County court house. The brick wall of the facade is punctuated by eight-above-eight small paned windows, flanked by wooden shutters. The windows that dot the two long side walls at the ground and second floor levels consist of six-above-six, small paned windows. Eight brick chimneys, four on each long side wall, rise along the eaves of the court house roof.

The facade on the structure's east end faces Juliana Street. Two square columns built into the red brick wall, known as pilasters, flank either side of two round, free-standing, Doric-style columns, all of which appear to hold up the lintel, frieze and pediment. The two central round columns stand in front of a recessed front-entrance portico. Despite their carved-stone-like appearance, the round columns are actually composed of thin, four-inch wide strips of wood positioned like barrel staves and glued together. Although a round 'bull's-eye' window was a standard element for the Greek Revival style, a half circle window accents the portion of brick wall above the frieze in the Bedford County court house. The brick wall of the facade is punctuated by eight-above-eight small paned windows, flanked by wooden shutters. The windows that dot the two long side walls at the ground and second floor levels consist of six-above-six, small paned windows. Eight brick chimneys, four on each long side wall, rise along the eaves of the court house roof.

![]() The entire building, with emphasis on the facade, almost looks like it was taken directly from a textbook on the Greek Revival style. It is truly a remarkable example of the style. The only architectural element that departs from a strict definition of the Greek Revival style is the steeple or cupola. A dome-topped circular bell tower sits upon a square base that occupies a portion of the roof close to the Juliana Street entrance. The bell tower, which in most Greek Revival structures would consist of a dome surmounted on short pillars, allowing the bell to be seen, is, in this example, enclosed with grilles. The domed top of the bell tower is painted a matte gold color. Although not known for certain, it is possible that the tower might be covered with sheet copper that oxidized over time and was painted gold to return it to its original appearance. Four large clock faces currently occupy walls of the steeple visible from the street level in all directions. In its early years there would have been only a single clock, undoubtedly occupying the east side.

The entire building, with emphasis on the facade, almost looks like it was taken directly from a textbook on the Greek Revival style. It is truly a remarkable example of the style. The only architectural element that departs from a strict definition of the Greek Revival style is the steeple or cupola. A dome-topped circular bell tower sits upon a square base that occupies a portion of the roof close to the Juliana Street entrance. The bell tower, which in most Greek Revival structures would consist of a dome surmounted on short pillars, allowing the bell to be seen, is, in this example, enclosed with grilles. The domed top of the bell tower is painted a matte gold color. Although not known for certain, it is possible that the tower might be covered with sheet copper that oxidized over time and was painted gold to return it to its original appearance. Four large clock faces currently occupy walls of the steeple visible from the street level in all directions. In its early years there would have been only a single clock, undoubtedly occupying the east side.

![]() In the early Nineteenth Century, the idea of constructing a 'floor' below the main, or first floor level was somewhat unique, but an idea that was growing and spreading. Starting in the 1790s, with William Strutt's use of a hot air furnace to heat his textile mill in Derby, England, the idea of heating large public buildings with steam rather than by open fireplaces led to the need for a room in which to locate the furnace. Underneath the building, in a cellar made the most sense for the placement of the furnace, and so basements became standard in public buildings. The court house in Bedford was constructed just at the time that the interests in both basement levels and steam heating were becoming popular. By employing steam heating, the 1828/29 Court House was a very modern building.

In the early Nineteenth Century, the idea of constructing a 'floor' below the main, or first floor level was somewhat unique, but an idea that was growing and spreading. Starting in the 1790s, with William Strutt's use of a hot air furnace to heat his textile mill in Derby, England, the idea of heating large public buildings with steam rather than by open fireplaces led to the need for a room in which to locate the furnace. Underneath the building, in a cellar made the most sense for the placement of the furnace, and so basements became standard in public buildings. The court house in Bedford was constructed just at the time that the interests in both basement levels and steam heating were becoming popular. By employing steam heating, the 1828/29 Court House was a very modern building.

![]() The exterior red brick walls of the 1828/29 court house were painted for many years. At the turn of the Twentieth Century the building was painted white with the windows' woodwork and the shutters being trimmed in green. At some time prior to 1970 the building was sandblasted to reveal the original red brick exterior walls.

The exterior red brick walls of the 1828/29 court house were painted for many years. At the turn of the Twentieth Century the building was painted white with the windows' woodwork and the shutters being trimmed in green. At some time prior to 1970 the building was sandblasted to reveal the original red brick exterior walls.

![]() Along the tops of each long wall, where they meet the roof's eaves, there are four tall and slender chimneys spaced equidistant along the tops of each wall. The chimneys on both long side walls appear to break through the line of the roof's eaves. No chimneys surmount the facade or the rear wall. All eight of the chimneys are exactly the same. Each is roughly five feet (i.e. twenty-six bricks) in height, thirty-two inches (i.e. four bricks) in length and twenty inches (i.e. two and one half bricks) in depth, the base of which is constructed of the same red brick as the wall from which it extends. At the top of the chimney there is a cast clay 'flue cap,' commonly called a 'chimney pot' because it is often cylindrical in shape. The flue cap adds another two feet to the overall height of the chimney. The flue cap is white in contrast to the red brick. The eight chimneys were built into, rather than attached to the outside of the walls. In actuality, only the flue pipes needed to be built inside the walls, and the chimneys only begin at the top of the walls where the flue pipes emerge. The steam heating system was utilized until the 1980's. By that time, the standard steam heating system, an oil-fired boiler, was replaced by a modern HVAC system.

Along the tops of each long wall, where they meet the roof's eaves, there are four tall and slender chimneys spaced equidistant along the tops of each wall. The chimneys on both long side walls appear to break through the line of the roof's eaves. No chimneys surmount the facade or the rear wall. All eight of the chimneys are exactly the same. Each is roughly five feet (i.e. twenty-six bricks) in height, thirty-two inches (i.e. four bricks) in length and twenty inches (i.e. two and one half bricks) in depth, the base of which is constructed of the same red brick as the wall from which it extends. At the top of the chimney there is a cast clay 'flue cap,' commonly called a 'chimney pot' because it is often cylindrical in shape. The flue cap adds another two feet to the overall height of the chimney. The flue cap is white in contrast to the red brick. The eight chimneys were built into, rather than attached to the outside of the walls. In actuality, only the flue pipes needed to be built inside the walls, and the chimneys only begin at the top of the walls where the flue pipes emerge. The steam heating system was utilized until the 1980's. By that time, the standard steam heating system, an oil-fired boiler, was replaced by a modern HVAC system.

![]() The main entrance, facing toward the east, and fronting on Juliana Street, is reached by mounting nine stone steps (on both sides) to a stone porch. [An old picture shows the steps as a single set positioned directly in front of the center of the porch. The date of the picture is unknown, and if it is a photograph is unknown.] Each step, consisting of a single, solid, cut limestone block, measures roughly one foot deep, seven feet wide and eight inches thick. The porch is constructed of even larger cut limestone blocks. The largest of the blocks each measure three feet wide and three feet & nine inches long. Their thickness is not known. In addition to three large blocks, the porch is constructed of a variety of smaller blocks in a puzzle pattern, with the smallest measuring one foot square. Also, it is not known whether the visible blocks rest on other large blocks or if they rest on ground fill. The question has been posed as to whether the porch might have originally been constructed of wood. The argument for the stone blocks that are currently in place being the only and original building material of the porch is given strength by the assumption that the same cut limestone blocks were used in the foundation. The style of the building, being very strictly Greek Revival, would have been adversely affected if the porch had been constructed of wood.

The main entrance, facing toward the east, and fronting on Juliana Street, is reached by mounting nine stone steps (on both sides) to a stone porch. [An old picture shows the steps as a single set positioned directly in front of the center of the porch. The date of the picture is unknown, and if it is a photograph is unknown.] Each step, consisting of a single, solid, cut limestone block, measures roughly one foot deep, seven feet wide and eight inches thick. The porch is constructed of even larger cut limestone blocks. The largest of the blocks each measure three feet wide and three feet & nine inches long. Their thickness is not known. In addition to three large blocks, the porch is constructed of a variety of smaller blocks in a puzzle pattern, with the smallest measuring one foot square. Also, it is not known whether the visible blocks rest on other large blocks or if they rest on ground fill. The question has been posed as to whether the porch might have originally been constructed of wood. The argument for the stone blocks that are currently in place being the only and original building material of the porch is given strength by the assumption that the same cut limestone blocks were used in the foundation. The style of the building, being very strictly Greek Revival, would have been adversely affected if the porch had been constructed of wood.

![]() The double doors which open into a circular shaped foyer are solid paneled doors with six small pane windows, or lights, in place of top panels. They are probably the original doors, but could be replacements since pictures of the court house from years past appear to show doors without windows of any sort. The entrance does not have sidelights, but it does have a transom over the doors consisting of a sixteen pane, fanlight window. Apart from a brass and candle chandelier, the only lighting for the foyer is the light coming in through the door windows and the fanlight above.

The double doors which open into a circular shaped foyer are solid paneled doors with six small pane windows, or lights, in place of top panels. They are probably the original doors, but could be replacements since pictures of the court house from years past appear to show doors without windows of any sort. The entrance does not have sidelights, but it does have a transom over the doors consisting of a sixteen pane, fanlight window. Apart from a brass and candle chandelier, the only lighting for the foyer is the light coming in through the door windows and the fanlight above.

![]() The foyer is circular shaped measuring twenty feet and six inches in diameter. It is a round room built within a square room. The curvilinear walls of the foyer are actually constructed of brick in the same manner and depth (approximately 1 foot) as the building's exterior walls. Like all of the first floor, it has a ceiling height of eleven feet. The primary purpose of the foyer, apart from serving as the room into which the main entrance leads, is to provide a space for two identical circular staircases. The twin staircases hug the outer wall in their climb to the second floor. The second floor landing only partially spans the entire space; it resembles a six-feet wide T-shaped bridge stretching from the east to the west walls with the top bar of the 'T' connecting two small chamber rooms on the north and south sides of the floor. The fact that the combined staircase and landing assembly is not supported by any post, pillar or column in the center, and that it has survived intact as such since 1828/29 is astounding. Handrails on the staircases' inside curves are composed of cherry wood, lathe-turned in the shape of a tube roughly four inches in diameter. The handrails are supported by simple straight, square balusters. Each handrail ends in a simple column newel post. The step treads attach to open stringers on the inside curve, each tread emphasized by a fancy skirting bracket moulding. Although currently covered with wall to wall carpeting, the staircase treads were probably exposed wood through the Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries.

The foyer is circular shaped measuring twenty feet and six inches in diameter. It is a round room built within a square room. The curvilinear walls of the foyer are actually constructed of brick in the same manner and depth (approximately 1 foot) as the building's exterior walls. Like all of the first floor, it has a ceiling height of eleven feet. The primary purpose of the foyer, apart from serving as the room into which the main entrance leads, is to provide a space for two identical circular staircases. The twin staircases hug the outer wall in their climb to the second floor. The second floor landing only partially spans the entire space; it resembles a six-feet wide T-shaped bridge stretching from the east to the west walls with the top bar of the 'T' connecting two small chamber rooms on the north and south sides of the floor. The fact that the combined staircase and landing assembly is not supported by any post, pillar or column in the center, and that it has survived intact as such since 1828/29 is astounding. Handrails on the staircases' inside curves are composed of cherry wood, lathe-turned in the shape of a tube roughly four inches in diameter. The handrails are supported by simple straight, square balusters. Each handrail ends in a simple column newel post. The step treads attach to open stringers on the inside curve, each tread emphasized by a fancy skirting bracket moulding. Although currently covered with wall to wall carpeting, the staircase treads were probably exposed wood through the Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries.

![]() At this point a bit of folklorish tradition should be mentioned in regard to the staircases. The steps are not horizontal; they lean, or tilt, down toward the inside curve. In fact, both staircases lean inward at the same angle, which is perhaps as much as five degrees from horizontal. That would not be the case if the tilting inward were due to simple age and wear and tear. Also the step treads are not pulling out from the wall, which functions as a closed stringer. As noted, both staircases possess the same inward tilt. It has been claimed that the staircases were intentionally built with the slight tilting, and that they did not change that way over the years through natural warping. The question would be "what benefit would the slight inward tilting serve, either aesthetically or physically?" A contemporary manufacturer of curved staircases, whose steps are horizontal, confuted the claim that anyone would intentionally construct a staircase in that manner because it would make the staircase inherently unsafe. It was noted that since both of the twin staircases have the same tilt and neither exhibit the effects of natural aging, such as would be exhibited if the treads were pulling away from the wall, it is possible that the carpenter who built the staircases simply miscalculated the length and curvature of the inside stringers. Once they were fabricated and the work of attaching the treads and risers was actually begun, it would have perhaps seemed too costly and/or time consuming to redo them. The slight tilting, though unintentional, might have been accepted from the very beginning out of the necessity of getting the job completed on time and under budget. Perhaps the commissioners at the time felt that the staircases would perform their function of permitting access to the second floor court room, despite the slight imperfection.

At this point a bit of folklorish tradition should be mentioned in regard to the staircases. The steps are not horizontal; they lean, or tilt, down toward the inside curve. In fact, both staircases lean inward at the same angle, which is perhaps as much as five degrees from horizontal. That would not be the case if the tilting inward were due to simple age and wear and tear. Also the step treads are not pulling out from the wall, which functions as a closed stringer. As noted, both staircases possess the same inward tilt. It has been claimed that the staircases were intentionally built with the slight tilting, and that they did not change that way over the years through natural warping. The question would be "what benefit would the slight inward tilting serve, either aesthetically or physically?" A contemporary manufacturer of curved staircases, whose steps are horizontal, confuted the claim that anyone would intentionally construct a staircase in that manner because it would make the staircase inherently unsafe. It was noted that since both of the twin staircases have the same tilt and neither exhibit the effects of natural aging, such as would be exhibited if the treads were pulling away from the wall, it is possible that the carpenter who built the staircases simply miscalculated the length and curvature of the inside stringers. Once they were fabricated and the work of attaching the treads and risers was actually begun, it would have perhaps seemed too costly and/or time consuming to redo them. The slight tilting, though unintentional, might have been accepted from the very beginning out of the necessity of getting the job completed on time and under budget. Perhaps the commissioners at the time felt that the staircases would perform their function of permitting access to the second floor court room, despite the slight imperfection.

![]() Beneath the twin staircases, located in the walls of the northeast and southeast corners of the foyer, are two doors measuring just six feet and six inches in height. Each of the doors permits access to a space between the one-foot thick outer wall and the one-foot thick curved inner wall. Essentially, each of the spaces is shaped like an isosceles triangle in which the longer side is a concave line. The space in the southeast corner is filled with a spiral staircase around a central post. That set of steps leads up into the bell tower. Although the bell is rung at the present-day by mechanical means, when the building was first built, the bell was rung by pulling on ropes. The gear or pulley assembly originally used in conjunction with the ropes to ring the bell is still in place although not in use. The steps to the bell tower are still in good shape, but anyone with claustrophobia or more than a 30-inch waist should not plan to try to navigate them. The space in the northeast corner currently provides access to piping for the HVAC unit. The space originally provided access to the hanging weight (said to have been a heavy rock) which kept the clock working. Despite the fact that four clock faces are seen from the outside, from the time that it was first installed, there was only a single clock mechanism. The first clock was purchased and installed in March 1857 for $250. The clock originally consisted of wooden gears, a pendulum and a hanging weight and like the smaller version known as a 'grandfather clock' before the advent of springs, the court house clock was kept in movement by the energy of the weight being transferred into the gears that moved the hands. The weight would be pulled, or rather ratcheted, up to the top by a winch and, aided by the ratchet mechanism, would work its way down to the bottom. The gradual descent of the weight permitted the clock to run eight days. In 1962 the clock was repaired by local jeweler, Courtney Mock. At the same time, Mock replaced the wooden hands of each of the four clock faces with ones cast from fiberglass reinforced plastic. The clock mechanism was replaced by a modern electronic mechanism as part of general renovations in 1987. The original clock gears were removed, presumably to be preserved, but their location today is not known.

Beneath the twin staircases, located in the walls of the northeast and southeast corners of the foyer, are two doors measuring just six feet and six inches in height. Each of the doors permits access to a space between the one-foot thick outer wall and the one-foot thick curved inner wall. Essentially, each of the spaces is shaped like an isosceles triangle in which the longer side is a concave line. The space in the southeast corner is filled with a spiral staircase around a central post. That set of steps leads up into the bell tower. Although the bell is rung at the present-day by mechanical means, when the building was first built, the bell was rung by pulling on ropes. The gear or pulley assembly originally used in conjunction with the ropes to ring the bell is still in place although not in use. The steps to the bell tower are still in good shape, but anyone with claustrophobia or more than a 30-inch waist should not plan to try to navigate them. The space in the northeast corner currently provides access to piping for the HVAC unit. The space originally provided access to the hanging weight (said to have been a heavy rock) which kept the clock working. Despite the fact that four clock faces are seen from the outside, from the time that it was first installed, there was only a single clock mechanism. The first clock was purchased and installed in March 1857 for $250. The clock originally consisted of wooden gears, a pendulum and a hanging weight and like the smaller version known as a 'grandfather clock' before the advent of springs, the court house clock was kept in movement by the energy of the weight being transferred into the gears that moved the hands. The weight would be pulled, or rather ratcheted, up to the top by a winch and, aided by the ratchet mechanism, would work its way down to the bottom. The gradual descent of the weight permitted the clock to run eight days. In 1962 the clock was repaired by local jeweler, Courtney Mock. At the same time, Mock replaced the wooden hands of each of the four clock faces with ones cast from fiberglass reinforced plastic. The clock mechanism was replaced by a modern electronic mechanism as part of general renovations in 1987. The original clock gears were removed, presumably to be preserved, but their location today is not known.

![]() The court house was extensively repaired and refurbished in the year 1930. The rooms were repainted, new light fixtures were installed and new carpeting was laid throughout. Records do not specifically note it, but the new light fixtures probably were installed in order to replace outdated and unsafe gas-fueled fixtures. Most people probably think that when the phrase 'new light fixtures' is used, it implies a different style or pattern, but in this case it more than likely implied a different type of lighting: electric. 'Modern' incandescent light bulbs, powered by electricity, did not become popular until the 1920's. So by the year 1930, the replacement of the gas-fueled lamps with electric-powered light bulbs would have been very modern for the times.

The court house was extensively repaired and refurbished in the year 1930. The rooms were repainted, new light fixtures were installed and new carpeting was laid throughout. Records do not specifically note it, but the new light fixtures probably were installed in order to replace outdated and unsafe gas-fueled fixtures. Most people probably think that when the phrase 'new light fixtures' is used, it implies a different style or pattern, but in this case it more than likely implied a different type of lighting: electric. 'Modern' incandescent light bulbs, powered by electricity, did not become popular until the 1920's. So by the year 1930, the replacement of the gas-fueled lamps with electric-powered light bulbs would have been very modern for the times.

![]() By the 1960's there was a growing need for additional space in the court house. The Commissioners began to look for nearby properties that would function as court house annexes. As part of that expansion, the adjacent building to the south, known as the Lyon House, was purchased and converted into an annex building. Prior to that purchase, the Lyon House had served as the home and hospital by Dr. Norman A. Timmons.

By the 1960's there was a growing need for additional space in the court house. The Commissioners began to look for nearby properties that would function as court house annexes. As part of that expansion, the adjacent building to the south, known as the Lyon House, was purchased and converted into an annex building. Prior to that purchase, the Lyon House had served as the home and hospital by Dr. Norman A. Timmons.

![]() In 2005, plans were formulated to erect a new structure to supplement the space and usage of the 1828/29 court house. In June it was announced in the Bedford Gazette that A. G. Cullen Construction, of Pittsburgh, had been awarded a $17.5 million contract for the general construction. John Hall Inc., of Ligonier won the bid for the HVAC (i.e. Heating Ventilation & Air Conditioning) contract. Church and Murdock Electric, of Johnstown would perform the electrical construction. Darr Construction won the contract for plumbing. It was estimated that the project would be completed within eighteen months. The mobile filing systems for use in many of the offices would be purchased separately but installed by Cullen.

In 2005, plans were formulated to erect a new structure to supplement the space and usage of the 1828/29 court house. In June it was announced in the Bedford Gazette that A. G. Cullen Construction, of Pittsburgh, had been awarded a $17.5 million contract for the general construction. John Hall Inc., of Ligonier won the bid for the HVAC (i.e. Heating Ventilation & Air Conditioning) contract. Church and Murdock Electric, of Johnstown would perform the electrical construction. Darr Construction won the contract for plumbing. It was estimated that the project would be completed within eighteen months. The mobile filing systems for use in many of the offices would be purchased separately but installed by Cullen.

![]() On the 14th of July 2005, the Bedford Gazette published an aerial view of the proposed court house complex. An addition to the rear of the Lyon House, built by Dr. Timmins, would be removed. The new structure would occupy the rear (west) portions of what had been designated as Lots #21 through #24 in Lukens' 1766 survey, and which had been used for the courthouse parking lot in recent years. The new structure would be three storeys tall and constructed of steel with a veneer of brick. It would connect the Lyon House with the original 1828/29 court house building forming a 'U' shape overall. The County parking lot to the west of Lafayette Avenue would be occupied by a new two level parking garage. By mid-February 2006, at least half of the structural steel was in place.

On the 14th of July 2005, the Bedford Gazette published an aerial view of the proposed court house complex. An addition to the rear of the Lyon House, built by Dr. Timmins, would be removed. The new structure would occupy the rear (west) portions of what had been designated as Lots #21 through #24 in Lukens' 1766 survey, and which had been used for the courthouse parking lot in recent years. The new structure would be three storeys tall and constructed of steel with a veneer of brick. It would connect the Lyon House with the original 1828/29 court house building forming a 'U' shape overall. The County parking lot to the west of Lafayette Avenue would be occupied by a new two level parking garage. By mid-February 2006, at least half of the structural steel was in place.

![]() Finally, on Thursday, 27 December 2007, a ribbon cutting ceremony was held by County officials to officially finalize the expansion project that had taken over two and a half years. The cost had risen to a final $20 million.

Finally, on Thursday, 27 December 2007, a ribbon cutting ceremony was held by County officials to officially finalize the expansion project that had taken over two and a half years. The cost had risen to a final $20 million.